This story originally appeared in the November, 2007 issue of PropTalk. Enjoy this Flashback Friday post!

The stark white motor launch quietly nudges alongside the 592-foot Panamanian-flagged cargo vessel,

Alioth Leader, moving slowly toward

Baltimore Harbor, and Alan Watts—a pony-tailed 53-year-old with tattooed arms and faded jeans—looks carefully fore and aft as he readies himself to board the ship.

A 30-foot rope ladder swings gently from the big car carrier’s port gunwale, and Watts deftly grabs a swaying lower rung and swiftly climbs his way to the top. A few minutes later, John J. Colgan, 58, wearing a white shirt, khakis, and a bright-yellow hardhat, climbs down the ladder and ducks into the launch’s spartan cabin. The boat motors off to an unmarked pier in Dundalk, MD.

There is no need to alert Homeland Security. It’s a normal transition for the pilots who help cargo ships and passenger liners transit the shoal-laden Chesapeake. The two men—along with dozens of other men and women like them—go through it frequently, sometimes several times a day.

Captain Colgan, a Bay pilot for the past 34 years, has just guided the

Alioth Leader through the 115-nautical-mile trip from Cape Henry—where the Atlantic Ocean meets the Bay—to the Patapsco River, which flows into Baltimore Harbor. Now Captain Watts, a docking pilot with extensive experience on tugboats, will direct the single-screw automobile-carrier—aided by a pair of large harbor tugs—to a berth at Atlantic Marine Terminal in Fairfield, MD, on the Patapsco’s south shore.

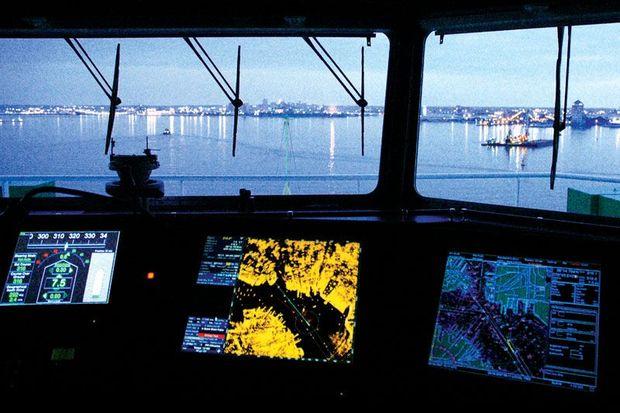

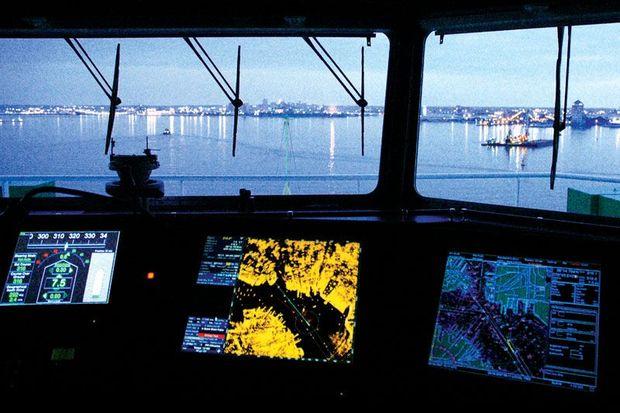

The pilots’ work requires them to cope with everything from high stress and danger in heavy weather and seas to the risk of becoming complacent in boring stretches of sunshine and calm. Both men think being a pilot is the best job in the world. “You just have to be really on your game and stay focused,” Watts says.

There are 62 certified pilots on the Maryland portion of the Bay, and together they’re part of a state-chartered monopoly. Under Maryland statute, the state Public Service Commission sets piloting fees, and the Baltimore-based Association of Maryland Pilots, which covers the territory from Cape Henry to the mouth of Delaware Bay, oversees the work schedules for Bay pilots and docking pilots. Pilots who operate in Virginia waters have a similar organization, the Virginia Pilot Association, created by the state legislature.

The pilots have been a fixture on the Bay since colonial days. The first Maryland pilots were authorized in 1733 by Charles Calvert, Lord Baltimore. In 1787, the state government set up rules laying out pilots’ duties and establishing a fee schedule. Today, all large commercial vessels transiting the Bay must take on a pilot, except U.S.-registered ships traveling solely between American ports. Maryland pilots guide more than 4000 such trips a year.

It isn’t easy to become a pilot in Maryland. Although it’s not a requirement, many applicants these days have bachelor’s degrees from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, NY, or a similar institution. Most have at least 10 years’ experience in the merchant marine. All must have Coast Guard licenses certifying them to be master or chief mate of any-sized ship.

Even then, the road is difficult. New entrants spend two years as apprentices, accompanying senior pilots on both Bay-transiting and docking. Then comes a three-year stint as a junior pilot, guiding medium-sized vessels with drafts of 28 feet or less, and, later, deeper boats with drafts up to 34 feet.

Senior pilots must pass a spate of written and on-the-job tests and reproduce from memory 10 large-sized nautical charts covering the waters from Cape Henry to the head of the Chesapeake.

“We give them a blank sheet of paper, with only the shoreline printed on it, and they have to fill in the buoys, the depth contours, the lights, the seabed characteristics, the wrecks, and any special regulations the chart contains,” explains Captain John Hamill, the association’s first-vice-president for operations. “Apprentices must complete more than 500 passages up and down the Bay and 30 with tugboats before they can sit for the exams,” Hamill says. “They’ll need 500 docking experiences in their logbooks before they can be designated full-fledged senior pilots.”

Pilots must renew their certifications every five years. Once a closed male bastion, the association now includes three women—two senior pilots and one junior.

As might be expected, the pilots’ biggest challenges are fog, heavy winds, sudden storms—and recreational boaters. Heavy fog makes it almost impossible for pilots to see more than a few hundred feet. The sheer height and length of today’s cargo vessels make them vulnerable to heavy winds—especially dangerous during docking. Many pilots just won’t go out in blows of 40 knots or more, meaning the ship will have to ride at anchor until the weather improves. Shipowners dislike such delays, because they cost them more money in wages and docking fees.

The problem with recreational boaters is a familiar one. Many pleasure boaters simply don’t realize that a big ship coming up the channel is a serious threat to them. With the merchant vessel’s bridge so far back on its hull, pilots usually can’t even see smaller vessels that are closer than a quarter- or half-mile ahead—too late to take evasive action. It usually takes a large ship a half-mile to a mile to stop. Even then, the vessel’s draft usually is so deep that there’s no place for it to go. (Note: Sailboats do not have the right-of-way over merchant ships in the Bay.) Most big ships must maintain a minimum speed to maintain control. “You don’t just hit the brakes,” Colgan says.

Finally, large merchant ships travel at speeds between 12 and 15 knots, and often close in much more quickly than many pleasure boaters reckon. “The best thing you can do when you see a merchant ship coming is to get out of her way—immediately,” says Hamill.

Not surprisingly, recreational traffic has often been the main factor in commercial accidents. Colgan was involved in one in 1980 in which the 680-foot containership he was piloting collided with a 44-foot pleasure boat whose crew was playing cards belowdeck. A Coast Guard investigation exonerated Colgan, but he recalls that news stories implied the merchant vessel had run the powerboat down.

Pilots’ workhours are as unpredictable as the weather. Although association members have a set rotation list, there’s often only a two-hour warning that they’ll have to be on duty, and they’re never sure how long a job will take. During slack periods, they may have several days off before they take a ship up or down the Bay again; but in busy times, they’re going strong, with as little as 12 hours between jobs.

The job also has its personal dangers. Foremost is the dangerous climb on the Jacob’s ladder, the rope stairway that hangs from the rails of cargo vessels and passenger liners. Although Maryland’s accident rate has been low, four pilots were killed across the United States last year, mostly in ladder-related mishaps.

Although Bay pilots and docking pilots don’t usually take on one another’s duties, the association has begun requiring new pilots to know enough about both skills so they can do either job in a pinch.

Colgan and Watts say they wouldn’t trade their gigs for anyone else’s. “I’d always wanted to be a pilot,” says Watts, who was born and raised in Dundalk, MD. “You’ve got to really love the challenge, but I held onto that dream, and it happened.

“To me,” he says, grinning, “it’s the best job in the world.”

About the Author: Art Pine is a freelance writer, USCG-licensed captain, and a longtime Chesapeake Bay boater.

A 30-foot rope ladder swings gently from the big car carrier’s port gunwale, and Watts deftly grabs a swaying lower rung and swiftly climbs his way to the top. A few minutes later, John J. Colgan, 58, wearing a white shirt, khakis, and a bright-yellow hardhat, climbs down the ladder and ducks into the launch’s spartan cabin. The boat motors off to an unmarked pier in Dundalk, MD.

There is no need to alert Homeland Security. It’s a normal transition for the pilots who help cargo ships and passenger liners transit the shoal-laden Chesapeake. The two men—along with dozens of other men and women like them—go through it frequently, sometimes several times a day.

Captain Colgan, a Bay pilot for the past 34 years, has just guided the Alioth Leader through the 115-nautical-mile trip from Cape Henry—where the Atlantic Ocean meets the Bay—to the Patapsco River, which flows into Baltimore Harbor. Now Captain Watts, a docking pilot with extensive experience on tugboats, will direct the single-screw automobile-carrier—aided by a pair of large harbor tugs—to a berth at Atlantic Marine Terminal in Fairfield, MD, on the Patapsco’s south shore.

The pilots’ work requires them to cope with everything from high stress and danger in heavy weather and seas to the risk of becoming complacent in boring stretches of sunshine and calm. Both men think being a pilot is the best job in the world. “You just have to be really on your game and stay focused,” Watts says.

A 30-foot rope ladder swings gently from the big car carrier’s port gunwale, and Watts deftly grabs a swaying lower rung and swiftly climbs his way to the top. A few minutes later, John J. Colgan, 58, wearing a white shirt, khakis, and a bright-yellow hardhat, climbs down the ladder and ducks into the launch’s spartan cabin. The boat motors off to an unmarked pier in Dundalk, MD.

There is no need to alert Homeland Security. It’s a normal transition for the pilots who help cargo ships and passenger liners transit the shoal-laden Chesapeake. The two men—along with dozens of other men and women like them—go through it frequently, sometimes several times a day.

Captain Colgan, a Bay pilot for the past 34 years, has just guided the Alioth Leader through the 115-nautical-mile trip from Cape Henry—where the Atlantic Ocean meets the Bay—to the Patapsco River, which flows into Baltimore Harbor. Now Captain Watts, a docking pilot with extensive experience on tugboats, will direct the single-screw automobile-carrier—aided by a pair of large harbor tugs—to a berth at Atlantic Marine Terminal in Fairfield, MD, on the Patapsco’s south shore.

The pilots’ work requires them to cope with everything from high stress and danger in heavy weather and seas to the risk of becoming complacent in boring stretches of sunshine and calm. Both men think being a pilot is the best job in the world. “You just have to be really on your game and stay focused,” Watts says.

There are 62 certified pilots on the Maryland portion of the Bay, and together they’re part of a state-chartered monopoly. Under Maryland statute, the state Public Service Commission sets piloting fees, and the Baltimore-based Association of Maryland Pilots, which covers the territory from Cape Henry to the mouth of Delaware Bay, oversees the work schedules for Bay pilots and docking pilots. Pilots who operate in Virginia waters have a similar organization, the Virginia Pilot Association, created by the state legislature.

The pilots have been a fixture on the Bay since colonial days. The first Maryland pilots were authorized in 1733 by Charles Calvert, Lord Baltimore. In 1787, the state government set up rules laying out pilots’ duties and establishing a fee schedule. Today, all large commercial vessels transiting the Bay must take on a pilot, except U.S.-registered ships traveling solely between American ports. Maryland pilots guide more than 4000 such trips a year.

It isn’t easy to become a pilot in Maryland. Although it’s not a requirement, many applicants these days have bachelor’s degrees from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, NY, or a similar institution. Most have at least 10 years’ experience in the merchant marine. All must have Coast Guard licenses certifying them to be master or chief mate of any-sized ship.

Even then, the road is difficult. New entrants spend two years as apprentices, accompanying senior pilots on both Bay-transiting and docking. Then comes a three-year stint as a junior pilot, guiding medium-sized vessels with drafts of 28 feet or less, and, later, deeper boats with drafts up to 34 feet.

There are 62 certified pilots on the Maryland portion of the Bay, and together they’re part of a state-chartered monopoly. Under Maryland statute, the state Public Service Commission sets piloting fees, and the Baltimore-based Association of Maryland Pilots, which covers the territory from Cape Henry to the mouth of Delaware Bay, oversees the work schedules for Bay pilots and docking pilots. Pilots who operate in Virginia waters have a similar organization, the Virginia Pilot Association, created by the state legislature.

The pilots have been a fixture on the Bay since colonial days. The first Maryland pilots were authorized in 1733 by Charles Calvert, Lord Baltimore. In 1787, the state government set up rules laying out pilots’ duties and establishing a fee schedule. Today, all large commercial vessels transiting the Bay must take on a pilot, except U.S.-registered ships traveling solely between American ports. Maryland pilots guide more than 4000 such trips a year.

It isn’t easy to become a pilot in Maryland. Although it’s not a requirement, many applicants these days have bachelor’s degrees from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, NY, or a similar institution. Most have at least 10 years’ experience in the merchant marine. All must have Coast Guard licenses certifying them to be master or chief mate of any-sized ship.

Even then, the road is difficult. New entrants spend two years as apprentices, accompanying senior pilots on both Bay-transiting and docking. Then comes a three-year stint as a junior pilot, guiding medium-sized vessels with drafts of 28 feet or less, and, later, deeper boats with drafts up to 34 feet.

Senior pilots must pass a spate of written and on-the-job tests and reproduce from memory 10 large-sized nautical charts covering the waters from Cape Henry to the head of the Chesapeake.

“We give them a blank sheet of paper, with only the shoreline printed on it, and they have to fill in the buoys, the depth contours, the lights, the seabed characteristics, the wrecks, and any special regulations the chart contains,” explains Captain John Hamill, the association’s first-vice-president for operations. “Apprentices must complete more than 500 passages up and down the Bay and 30 with tugboats before they can sit for the exams,” Hamill says. “They’ll need 500 docking experiences in their logbooks before they can be designated full-fledged senior pilots.”

Pilots must renew their certifications every five years. Once a closed male bastion, the association now includes three women—two senior pilots and one junior.

As might be expected, the pilots’ biggest challenges are fog, heavy winds, sudden storms—and recreational boaters. Heavy fog makes it almost impossible for pilots to see more than a few hundred feet. The sheer height and length of today’s cargo vessels make them vulnerable to heavy winds—especially dangerous during docking. Many pilots just won’t go out in blows of 40 knots or more, meaning the ship will have to ride at anchor until the weather improves. Shipowners dislike such delays, because they cost them more money in wages and docking fees.

Senior pilots must pass a spate of written and on-the-job tests and reproduce from memory 10 large-sized nautical charts covering the waters from Cape Henry to the head of the Chesapeake.

“We give them a blank sheet of paper, with only the shoreline printed on it, and they have to fill in the buoys, the depth contours, the lights, the seabed characteristics, the wrecks, and any special regulations the chart contains,” explains Captain John Hamill, the association’s first-vice-president for operations. “Apprentices must complete more than 500 passages up and down the Bay and 30 with tugboats before they can sit for the exams,” Hamill says. “They’ll need 500 docking experiences in their logbooks before they can be designated full-fledged senior pilots.”

Pilots must renew their certifications every five years. Once a closed male bastion, the association now includes three women—two senior pilots and one junior.

As might be expected, the pilots’ biggest challenges are fog, heavy winds, sudden storms—and recreational boaters. Heavy fog makes it almost impossible for pilots to see more than a few hundred feet. The sheer height and length of today’s cargo vessels make them vulnerable to heavy winds—especially dangerous during docking. Many pilots just won’t go out in blows of 40 knots or more, meaning the ship will have to ride at anchor until the weather improves. Shipowners dislike such delays, because they cost them more money in wages and docking fees.

The problem with recreational boaters is a familiar one. Many pleasure boaters simply don’t realize that a big ship coming up the channel is a serious threat to them. With the merchant vessel’s bridge so far back on its hull, pilots usually can’t even see smaller vessels that are closer than a quarter- or half-mile ahead—too late to take evasive action. It usually takes a large ship a half-mile to a mile to stop. Even then, the vessel’s draft usually is so deep that there’s no place for it to go. (Note: Sailboats do not have the right-of-way over merchant ships in the Bay.) Most big ships must maintain a minimum speed to maintain control. “You don’t just hit the brakes,” Colgan says.

Finally, large merchant ships travel at speeds between 12 and 15 knots, and often close in much more quickly than many pleasure boaters reckon. “The best thing you can do when you see a merchant ship coming is to get out of her way—immediately,” says Hamill.

Not surprisingly, recreational traffic has often been the main factor in commercial accidents. Colgan was involved in one in 1980 in which the 680-foot containership he was piloting collided with a 44-foot pleasure boat whose crew was playing cards belowdeck. A Coast Guard investigation exonerated Colgan, but he recalls that news stories implied the merchant vessel had run the powerboat down.

Pilots’ workhours are as unpredictable as the weather. Although association members have a set rotation list, there’s often only a two-hour warning that they’ll have to be on duty, and they’re never sure how long a job will take. During slack periods, they may have several days off before they take a ship up or down the Bay again; but in busy times, they’re going strong, with as little as 12 hours between jobs.

The problem with recreational boaters is a familiar one. Many pleasure boaters simply don’t realize that a big ship coming up the channel is a serious threat to them. With the merchant vessel’s bridge so far back on its hull, pilots usually can’t even see smaller vessels that are closer than a quarter- or half-mile ahead—too late to take evasive action. It usually takes a large ship a half-mile to a mile to stop. Even then, the vessel’s draft usually is so deep that there’s no place for it to go. (Note: Sailboats do not have the right-of-way over merchant ships in the Bay.) Most big ships must maintain a minimum speed to maintain control. “You don’t just hit the brakes,” Colgan says.

Finally, large merchant ships travel at speeds between 12 and 15 knots, and often close in much more quickly than many pleasure boaters reckon. “The best thing you can do when you see a merchant ship coming is to get out of her way—immediately,” says Hamill.

Not surprisingly, recreational traffic has often been the main factor in commercial accidents. Colgan was involved in one in 1980 in which the 680-foot containership he was piloting collided with a 44-foot pleasure boat whose crew was playing cards belowdeck. A Coast Guard investigation exonerated Colgan, but he recalls that news stories implied the merchant vessel had run the powerboat down.

Pilots’ workhours are as unpredictable as the weather. Although association members have a set rotation list, there’s often only a two-hour warning that they’ll have to be on duty, and they’re never sure how long a job will take. During slack periods, they may have several days off before they take a ship up or down the Bay again; but in busy times, they’re going strong, with as little as 12 hours between jobs.

The job also has its personal dangers. Foremost is the dangerous climb on the Jacob’s ladder, the rope stairway that hangs from the rails of cargo vessels and passenger liners. Although Maryland’s accident rate has been low, four pilots were killed across the United States last year, mostly in ladder-related mishaps.

Although Bay pilots and docking pilots don’t usually take on one another’s duties, the association has begun requiring new pilots to know enough about both skills so they can do either job in a pinch.

Colgan and Watts say they wouldn’t trade their gigs for anyone else’s. “I’d always wanted to be a pilot,” says Watts, who was born and raised in Dundalk, MD. “You’ve got to really love the challenge, but I held onto that dream, and it happened.

“To me,” he says, grinning, “it’s the best job in the world.”

About the Author: Art Pine is a freelance writer, USCG-licensed captain, and a longtime Chesapeake Bay boater.

The job also has its personal dangers. Foremost is the dangerous climb on the Jacob’s ladder, the rope stairway that hangs from the rails of cargo vessels and passenger liners. Although Maryland’s accident rate has been low, four pilots were killed across the United States last year, mostly in ladder-related mishaps.

Although Bay pilots and docking pilots don’t usually take on one another’s duties, the association has begun requiring new pilots to know enough about both skills so they can do either job in a pinch.

Colgan and Watts say they wouldn’t trade their gigs for anyone else’s. “I’d always wanted to be a pilot,” says Watts, who was born and raised in Dundalk, MD. “You’ve got to really love the challenge, but I held onto that dream, and it happened.

“To me,” he says, grinning, “it’s the best job in the world.”

About the Author: Art Pine is a freelance writer, USCG-licensed captain, and a longtime Chesapeake Bay boater.