As boaters trying to keep up with updated marine safety equipment, when we hear about new innovations, we find ourselves asking, “Do you remember the old way?” Sometimes “the old way” refers to only a year or two ago, but when you look farther into the “wayback machine,” it’s astonishing how equipment and electronics have evolved and how much easier and safer our boating lives have become. Here’s a peek at what used to be the norm and the modern iterations:

Where are we?

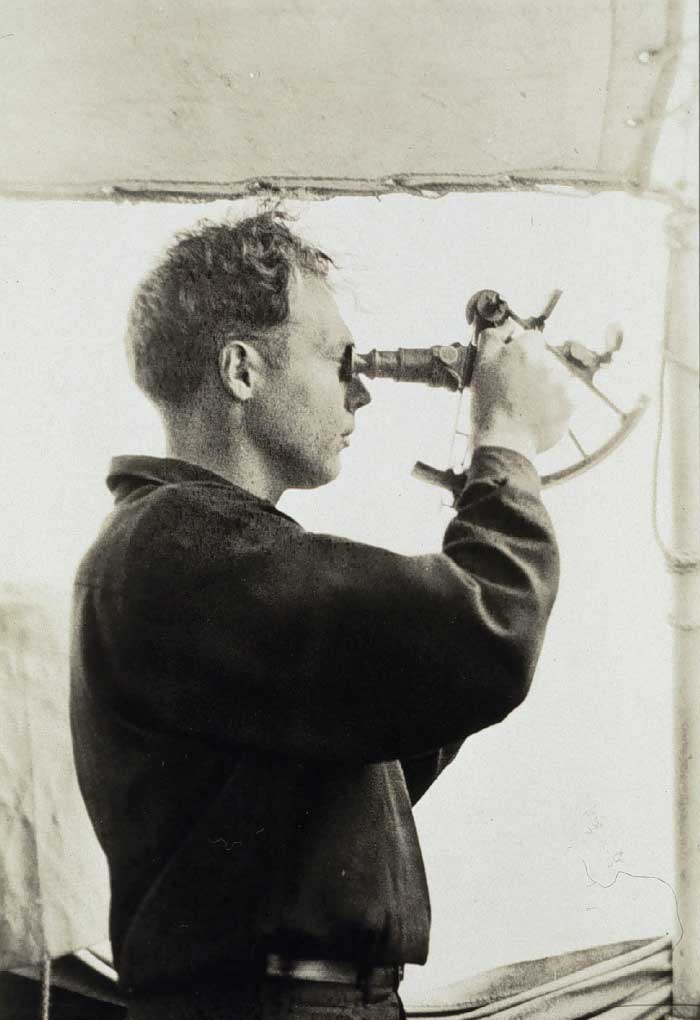

Then (and Now): Sextant

Dating back to the early 1700s, the sextant was used to determine latitude and longitude at sea by measuring angular distances, especially the altitudes of sun, moon, and stars. These days, anyone who’s ever tried to use this instrument has likely participated in a celestial navigation class, taken a “noon sight” of the horizon, flipped through an almanac, and remembered their math skills to figure out the distance. Since the sextant requires no electricity to run, this instrument remains a practical navigation backup tool and may save your life if you experience system failures at sea. But you must know how to use it.

Then: RDF

Radio-directed frequency (RDF), once the primary form of marine navigation, involved strings of beacons forming airwaves from airport to airport. Marine non-directional beacons and AM radio broadcast stations provided navigational assistance to small watercraft approaching a landfall. AM radio stations were required to broadcast their station identifier once per hour for use by pilots and mariners as an aid to navigation. LORAN (another defunct navigational tool) replaced this navigational beacon technology in the 1970s.

Now: GPS

The Global Positioning System (GPS), a U.S.-owned utility, provides users with positioning, navigation, and timing services. As part of the global information infrastructure, the free, open, and dependable satellite-based navigation system has changed almost every aspect of our lives, including, of course, finding our way safely up and down the Chesapeake, especially when the visibility is low due to fog or stormy weather.

As well as using chartplotters that integrate GPS data and electronic charts to plot their courses, modern mariners may easily note their positions as well as use their smartphone to text their exact coordinates to their raftup or fishing buddies. Knowing your exact position and how to communicate it effectively is critical in emergency situations.

Now: Charts

Paper charts are not yet extinct, but most modern boaters have gone digital! With the ease of uploading electronic charts systems such as Navionics to your boat’s electronics or your iPad, rolling out an old-fashioned chart seems quaint. Smart mariners will keep a version of a paper chartbook on hand, as it does not require batteries, electricity, or a reliable satellite to operate, and you never know when your electrical systems will fail you, or after a surprise storm you’ll need to find your way home.

Where are you?

Then: Crow’s nest

To the crow’s nest ye go, matey! Imagine mariners of the past having nothing more than a mast to climb up and crude binoculars to spot other ships, islands, or shoals, and detect upcoming dangers.

Now: AIS

The automatic identification system (AIS), an automatic tracking system, uses transceivers on ships and is used by vessel traffic services. The same system that companies use to monitor their ship’s progress around the world and prevents collisions at sea allows you to follow your friends’ progress as they take their cruising boat from Baltimore to Solomons for the weekend. It also enables you to see the ship traffic coming up and down the shipping lane in the Bay.

Even if your boat is not equipped with AIS, you may click to marinetraffic.com and zoom into your part of the Chesapeake to identify a ship (and its position, course, and speed) or see if any shipping traffic is expected (the app gives you more detailed information than the web version). And if your boat’s electronics or cell phone fail you, it’s helpful to keep binoculars onboard to spot ships, other pleasure craft, and aids to navigation.

Then: Morse Code

The idea of texting started back in the late 1800s when Guglielmo Marconi invented the first radio transmitters and receivers. This “wireless telegraphony era” lasted through the first World War. Amplitude modulation (AM) radiotelephony followed, allowing sound to be transmitted by radio. Radio telegraphy transmitted information by pulses of radio waves of two different lengths—dots and dashes—which spelled out text messages usually in Morse code.

Now: VHF Radio

Marine VHF radio is a worldwide system of two-way radio transceivers on ships and watercraft used for bidirectional voice communication from ship-to-ship, ship-to-shore, and in certain circumstances ship-to-aircraft. It’s a very effective communication tool when used correctly (BoatUS Foundation offers a reasonably priced online course). Although on a calm summer’s day you may communicate with fellow boaters by cell phone more than anything, having a VHF onboard and knowing how to use it are important tools for the safe boaters’ kit.

What floats?

Then: Lifejackets

Various forms of personal floatation devices (PFD) or lifejackets have been around since the 1800s for military and aircraft use, but it took awhile for the recreational boating consumers to have options. Many of our readers can remember putting an orange “type II” PFD over their heads and buckling up. Such PFDs are still in use, and you’ll find them as extras on many boats you board—although there are more comfortable and fashionable options.

Now: Lifejackets

Modern boaters wear various personal floatation devices (PFD), depending on the type of boating they do. Kayak anglers wear vest-style lifejackets, while cruisers prefer inflatable PFDs. A standup paddleboarder on a calm summer day may opt for a belt-style, manually operated inflatable. On the heavy-duty end are flotation coats, which work well for boaters standing watch or working on deck in cold and windy conditions. They offer flotation when fully immersed in water and are classified as USCG-approved type III inflatable PFDs.

This is part one in a three-part safety series. Stay tuned for part two in our March issue.