We had been cranking the little Westerbeke diesel engine for 10 minutes, on and off, and now the starter was hot to the touch and the batteries were getting low. The little four-cylinder engine seemed to want to start, almost kicked over a couple of times, but then wouldn’t. It hissed its displeasure between tries.

“I don’t get it,” Dave, my moonlighting engine guy, muttered, shaking his head. In frustration, he began disassembling the fuel pump on the side of the engine, blowing through it, sucking fuel through the channels, something you always would rather see someone else do rather than yourself. All of a sudden, he got something unpleasant in his mouth; “P-taaa!” he spat, and out came a chunk of rust the size of a pea. “What’s that?” I asked.

“It was right there in the pump, blocking the fuel flow,” he replied, spitting some more. I wondered aloud how a chunk of rust like that could get into the pump, since after all, it would never have made it through the fuel filter. “Maybe it grew there,” Dave surmised, “You know, like a kidney stone.” Once the pump was re-assembled, the little diesel roared to life and chirped happily as though there had never been a problem.

Dirty fuel or dirty emissions?

It has always seemed odd to me that diesel engines, touted as being more reliable and simpler in mechanical features than gasoline engines, nevertheless operate on what many consider to be the dirtiest fuel of engine fuels, and therefore are sometimes problematic.

“Diesel is the dirtiest fuel,” Dave says, but then I ask, “Why is this so?”

We do know that bacteria, mold, and yeast love to grow in it, unlike gasoline, which makes it important in the warm months to put biocide and other fuel conditioners in the diesel fuel tanks and always have spare fuel filters in reserve.

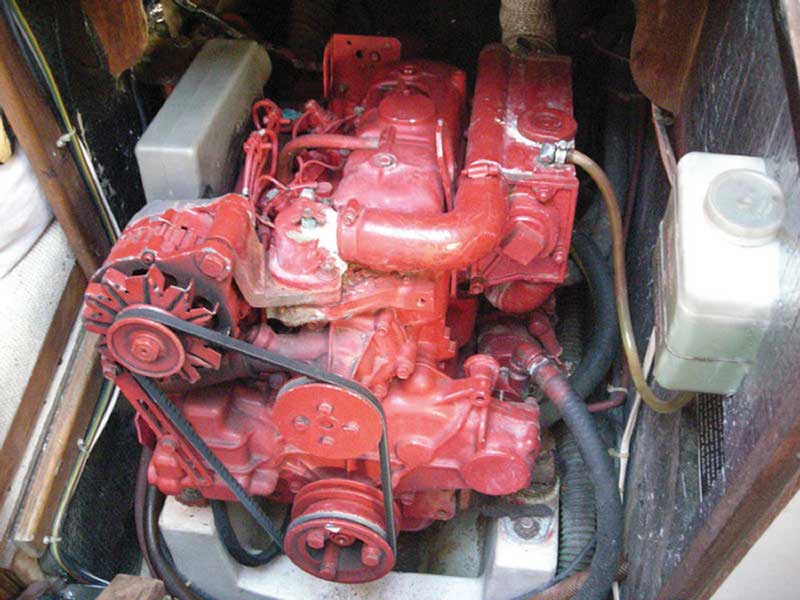

I had been so long with gasoline engines that when I bought my antique fixer-upper wooden yawl with an auxiliary diesel engine in it, my first diesel, I was a bit perplexed. I didn’t trust it because I didn’t understand it. Yes, I knew why it didn’t have spark plugs or ignition wires. But it also had other odd features, such as a high-pressure fuel pump that one was supposed to ‘never touch, or for God’s sake; never open or disassemble’ as one fellow boater told me.

Indeed, if it ever ran out of fuel, I would have to ‘bleed’ the air out of the thing using several ‘bleed screws’ in a pre-determined sequence. After losing a couple of nights’ sleep worrying about how I would or could service it and having tried to read the (clearly deceptively) simple engine manual, I threw in the towel and signed up for a one-day basic course in diesel engines at Massachusetts Maritime Academy.

Once in class, I was relieved, and delighted, to discover that the little engine that we had to pull apart, reassemble, and even start was an old Westerbeke model very similar to my own. Now, I thought, I would at last understand the deepest secrets of the mystical Diesel Engine. But I was naive; the poor little Westerbeke in the classroom, having been disassembled and reassembled hundreds and hundreds of times, was now as loose, clean, and docile as a lamb; unlike my own engine, and like many other small diesel auxiliary engines which, as petulant as cats, have individual minds of their own and will occasionally do as they please.

In my humble opinion, reliable operation of a diesel auxiliary engine requires the cleanest possible fuel. If you Google “Is diesel a dirty fuel?,” the preponderance of results will be primarily websites, blogs, and articles coming to the defense of diesel as the new ‘green’ fuel but all related to emissions.

As a boat owner running a small diesel engine, there is little that I can do with regard to controlling the emissions of my engine, other than making sure that the engine is tuned properly and burning its fuel with maximum efficiency. I am more concerned, perhaps, with reliably powering against a foul tide into the safety of an inlet in a cross-sea and rising gale. But on the subject of the ‘dirty’ fuel or dirty diesel, nobody seems to be addressing the question or the topic of the fuel itself which, in my experience, needs attention and care if it is not going to turn into as one friend put it, “a tank full of black ice cream” on a summer day.

One can purchase and install secondary diesel fuel cleaners or fuel polishers that clean the fuel on its way from the fuel tank to your engine. Companies including Reverso Pumps, Algae-X, ESI Total Fuel Management, Gulf Coast Filters, Walker Engineering, and others supply them in various capacities.

Mulling the thought of taking my boat to the Caribbean one winter, I asked some boating friends who participated annually in a Caribbean-bound rally, whether I might need to install a fuel polishing system beforehand. They aren’t cheap, and require engine room space, which may be at a premium in a sailboat. My friend’s response was that, generally, the quality of fuel in the U.S. is adequate to avoid the need for such a system, and even most popular destinations in the Caribbean have clean fuel, in part because so much of it is purchased there that there is no opportunity for it to ‘stale.’ But for auxiliary cruisers visiting out-of-the-way destinations in Central America or lesser-visited Caribbean haunts, having a diesel fuel polishing system is advisable, because you may never know when you may pump in a batch of bad stuff.

Tanks

The Achilles’ heel of any fuel system, I feel, is the fuel tank. You wouldn’t drink nice spring water out of a rusty can, so why would you let your engine sip fuel out of a dirty, corroding tank full of sediment? It makes no sense. When I re-built my 1930 gaff yawl, after ripping off the rotted transom, I pulled out the corroding galvanized sheet steel fuel tanks and replaced them with permanent molded polypropylene tanks made by Moeller Marine before rebuilding and replanking the transom. A singular advantage of having a translucent tank material is that if you ever mistrust your fuel gauge, climbing aft with a powerful flashlight will let you see right away how full the tank is.

Filters

For diesel fuel and engines, you need a fuel/water separator, but you especially need spare paper cartridge filters, RACORs, or whatever your system uses, always several more than you think, especially if embarking on a long passage over open water. This message was driven home to me on a catamaran delivery to St. Martin a number of years ago. The owner had decided to convert the starboard side metal water tank into an extra fuel tank by draining it, reconfiguring the hoses, and filling it with red diesel fuel. Of course, all the happy microorganisms that like to grow in diesel found themselves to be guests at a sumptuous dinner.

We didn’t have spare filters, maybe two, one for each of the two small engines. We were racing to reach St. Martin before a forecasted gale in a few days (which became Hurricane Lenny), and for every couple of hours of running time, the fuel filters had to be pulled and swapped and the dirty ones washed out in warm water and detergent and dried so as to be re-usable. They became brown and hairy from being washed so many times. This seemingly endless nightmare cycle continued for two days, punctuated by the need to occasionally crawl astern in rough seas and climb down into the hot, dark, cramped, oily engine compartments to bleed and re-start each engine if it became air-bound during filter changeout.

Small auxiliary diesel engines are extremely reliable, dependable servants especially under adverse conditions. To keep them that way, keep their fuel and fuel pathways clean, and stored fuel properly conditioned.

About the Author: Capt. Mike Martel holds a 100-ton Master's license and is a lifelong boating and marine industry enthusiast. He enjoys delivering boats to destinations along the East Coast and to the Caribbean and writing about his experiences.