When Fort McHenry was built, masonry replaced the former earthenware walls, and more cannons were added in the upper and lower battery, and for good reason. Baltimore’s safety would soon be put to the test during the War of 1812. While the British were delayed at North Point, Fort McHenry could be properly readied for the attack, and the ensuing American victory inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem “Defence of Fort McHenry.” That poem later became the lyrics for “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In 1828, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began laying the track, that would eventually connect to Port warehouses in Locust Point in 1845. Supply and demand for imported goods continued to grow, making Baltimore the gateway to an expanding nation. Ship production also increased steadily during this time.

With increasing activity in the harbor, it soon became clear that the width and depth of the port would have to be expanded. In 1830 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers surveyed Baltimore Harbor and established the central depth at 17 feet. While the harbor had been dredged up until this point, it was the River and Harbor Act of 1852 that authorized “dredging to obtain specific dimensions.” This allowed for a channel to be dredged 22 feet deep and 150 feet wide from Fort McHenry to Swan Point. Brewerton Channel was created in 1869 in order to decrease sediment accumulations and reduce the need for future dredging. As the port continued to grow, new channels were created as needed.

Today, the main channel measures 51 feet deep and 700 feet across. In 2001 Brewerton Channel was expanded to 50 feet deep and 700 feet across. On June 1, 2006, in celebration of the Port’s 300th anniversary, the Governor named the state’s public marine terminals the “Helen Delich Bentley Port of Baltimore.” By mid-2015, the access channel to the Seagirt Terminal was widened to accommodate the world’s largest container ships. And with the expansion complete on the Panama Canal, it is only a matter of time before Baltimore begins to see even more ships. Baltimore is only one of three East Coast ports that can handle the new “mega ships” that will be traversing the canal.

When Fort McHenry was built, masonry replaced the former earthenware walls, and more cannons were added in the upper and lower battery, and for good reason. Baltimore’s safety would soon be put to the test during the War of 1812. While the British were delayed at North Point, Fort McHenry could be properly readied for the attack, and the ensuing American victory inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem “Defence of Fort McHenry.” That poem later became the lyrics for “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In 1828, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began laying the track, that would eventually connect to Port warehouses in Locust Point in 1845. Supply and demand for imported goods continued to grow, making Baltimore the gateway to an expanding nation. Ship production also increased steadily during this time.

With increasing activity in the harbor, it soon became clear that the width and depth of the port would have to be expanded. In 1830 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers surveyed Baltimore Harbor and established the central depth at 17 feet. While the harbor had been dredged up until this point, it was the River and Harbor Act of 1852 that authorized “dredging to obtain specific dimensions.” This allowed for a channel to be dredged 22 feet deep and 150 feet wide from Fort McHenry to Swan Point. Brewerton Channel was created in 1869 in order to decrease sediment accumulations and reduce the need for future dredging. As the port continued to grow, new channels were created as needed.

Today, the main channel measures 51 feet deep and 700 feet across. In 2001 Brewerton Channel was expanded to 50 feet deep and 700 feet across. On June 1, 2006, in celebration of the Port’s 300th anniversary, the Governor named the state’s public marine terminals the “Helen Delich Bentley Port of Baltimore.” By mid-2015, the access channel to the Seagirt Terminal was widened to accommodate the world’s largest container ships. And with the expansion complete on the Panama Canal, it is only a matter of time before Baltimore begins to see even more ships. Baltimore is only one of three East Coast ports that can handle the new “mega ships” that will be traversing the canal.

Tuesday, August 2, 2016 - 09:00

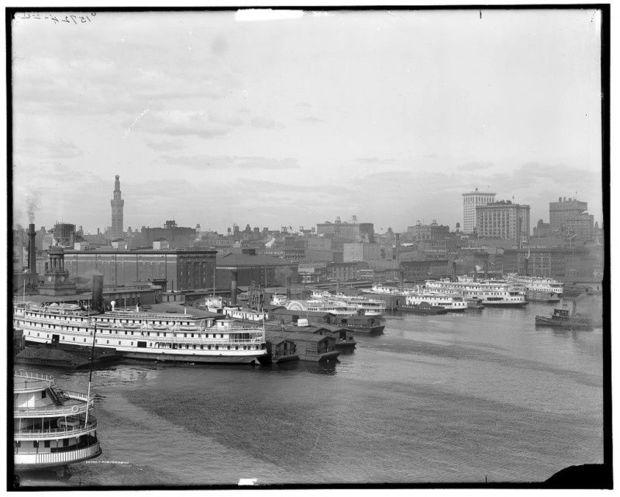

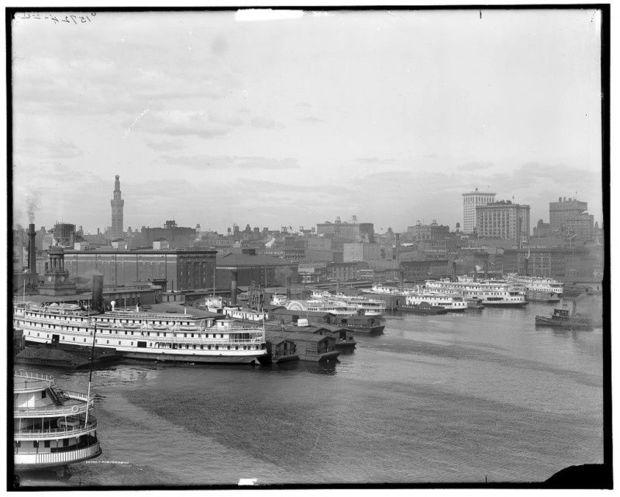

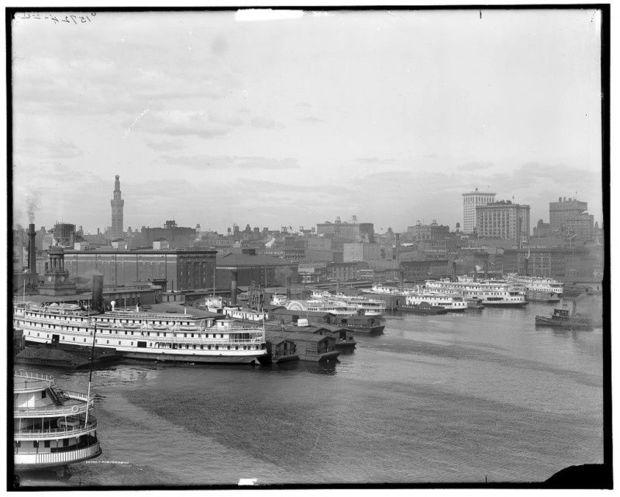

In 1608, Captain John Smith and a crew of 14 men set out on a small wooden boat to map the Chesapeake Bay. They traveled first up the Eastern Shore; then headed west and explored as far north as the Patapsco River (on that first voyage). Some years later, the port began to form around the tobacco trade, and Baltimore became an access point for trade with England. In 1706, the Port of Baltimore was designated a port of entry by the General Assembly.

At the time, Fells Point was the deepest part of the natural harbor and quickly became the city’s shipbuilding center. The shipyards soon gained renown for the construction of Baltimore Clippers, notorious as raiders and privateers, and for frigates of the Continental Navy. Over 800 ships were commissioned from 1784 to 1821. In 1773 the area was incorporated into Baltimore City.

During the Revolutionary War, Baltimore began to grow into a true city, and the port became a center for trade with the West Indies (which helped to support the war effort). But the port’s success also meant the potential for attack, so an earthenware fort, known as Fort Whetstone, was erected in 1776. (This would later be replaced by Fort McHenry in 1794.) By 1783, Wardens of the Port were appointed to authorize wharf construction, clear waterways, and collect duties from vessels traversing the port.

When Fort McHenry was built, masonry replaced the former earthenware walls, and more cannons were added in the upper and lower battery, and for good reason. Baltimore’s safety would soon be put to the test during the War of 1812. While the British were delayed at North Point, Fort McHenry could be properly readied for the attack, and the ensuing American victory inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem “Defence of Fort McHenry.” That poem later became the lyrics for “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In 1828, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began laying the track, that would eventually connect to Port warehouses in Locust Point in 1845. Supply and demand for imported goods continued to grow, making Baltimore the gateway to an expanding nation. Ship production also increased steadily during this time.

With increasing activity in the harbor, it soon became clear that the width and depth of the port would have to be expanded. In 1830 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers surveyed Baltimore Harbor and established the central depth at 17 feet. While the harbor had been dredged up until this point, it was the River and Harbor Act of 1852 that authorized “dredging to obtain specific dimensions.” This allowed for a channel to be dredged 22 feet deep and 150 feet wide from Fort McHenry to Swan Point. Brewerton Channel was created in 1869 in order to decrease sediment accumulations and reduce the need for future dredging. As the port continued to grow, new channels were created as needed.

Today, the main channel measures 51 feet deep and 700 feet across. In 2001 Brewerton Channel was expanded to 50 feet deep and 700 feet across. On June 1, 2006, in celebration of the Port’s 300th anniversary, the Governor named the state’s public marine terminals the “Helen Delich Bentley Port of Baltimore.” By mid-2015, the access channel to the Seagirt Terminal was widened to accommodate the world’s largest container ships. And with the expansion complete on the Panama Canal, it is only a matter of time before Baltimore begins to see even more ships. Baltimore is only one of three East Coast ports that can handle the new “mega ships” that will be traversing the canal.

When Fort McHenry was built, masonry replaced the former earthenware walls, and more cannons were added in the upper and lower battery, and for good reason. Baltimore’s safety would soon be put to the test during the War of 1812. While the British were delayed at North Point, Fort McHenry could be properly readied for the attack, and the ensuing American victory inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem “Defence of Fort McHenry.” That poem later became the lyrics for “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In 1828, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began laying the track, that would eventually connect to Port warehouses in Locust Point in 1845. Supply and demand for imported goods continued to grow, making Baltimore the gateway to an expanding nation. Ship production also increased steadily during this time.

With increasing activity in the harbor, it soon became clear that the width and depth of the port would have to be expanded. In 1830 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers surveyed Baltimore Harbor and established the central depth at 17 feet. While the harbor had been dredged up until this point, it was the River and Harbor Act of 1852 that authorized “dredging to obtain specific dimensions.” This allowed for a channel to be dredged 22 feet deep and 150 feet wide from Fort McHenry to Swan Point. Brewerton Channel was created in 1869 in order to decrease sediment accumulations and reduce the need for future dredging. As the port continued to grow, new channels were created as needed.

Today, the main channel measures 51 feet deep and 700 feet across. In 2001 Brewerton Channel was expanded to 50 feet deep and 700 feet across. On June 1, 2006, in celebration of the Port’s 300th anniversary, the Governor named the state’s public marine terminals the “Helen Delich Bentley Port of Baltimore.” By mid-2015, the access channel to the Seagirt Terminal was widened to accommodate the world’s largest container ships. And with the expansion complete on the Panama Canal, it is only a matter of time before Baltimore begins to see even more ships. Baltimore is only one of three East Coast ports that can handle the new “mega ships” that will be traversing the canal.

When Fort McHenry was built, masonry replaced the former earthenware walls, and more cannons were added in the upper and lower battery, and for good reason. Baltimore’s safety would soon be put to the test during the War of 1812. While the British were delayed at North Point, Fort McHenry could be properly readied for the attack, and the ensuing American victory inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem “Defence of Fort McHenry.” That poem later became the lyrics for “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In 1828, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began laying the track, that would eventually connect to Port warehouses in Locust Point in 1845. Supply and demand for imported goods continued to grow, making Baltimore the gateway to an expanding nation. Ship production also increased steadily during this time.

With increasing activity in the harbor, it soon became clear that the width and depth of the port would have to be expanded. In 1830 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers surveyed Baltimore Harbor and established the central depth at 17 feet. While the harbor had been dredged up until this point, it was the River and Harbor Act of 1852 that authorized “dredging to obtain specific dimensions.” This allowed for a channel to be dredged 22 feet deep and 150 feet wide from Fort McHenry to Swan Point. Brewerton Channel was created in 1869 in order to decrease sediment accumulations and reduce the need for future dredging. As the port continued to grow, new channels were created as needed.

Today, the main channel measures 51 feet deep and 700 feet across. In 2001 Brewerton Channel was expanded to 50 feet deep and 700 feet across. On June 1, 2006, in celebration of the Port’s 300th anniversary, the Governor named the state’s public marine terminals the “Helen Delich Bentley Port of Baltimore.” By mid-2015, the access channel to the Seagirt Terminal was widened to accommodate the world’s largest container ships. And with the expansion complete on the Panama Canal, it is only a matter of time before Baltimore begins to see even more ships. Baltimore is only one of three East Coast ports that can handle the new “mega ships” that will be traversing the canal.

When Fort McHenry was built, masonry replaced the former earthenware walls, and more cannons were added in the upper and lower battery, and for good reason. Baltimore’s safety would soon be put to the test during the War of 1812. While the British were delayed at North Point, Fort McHenry could be properly readied for the attack, and the ensuing American victory inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem “Defence of Fort McHenry.” That poem later became the lyrics for “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In 1828, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began laying the track, that would eventually connect to Port warehouses in Locust Point in 1845. Supply and demand for imported goods continued to grow, making Baltimore the gateway to an expanding nation. Ship production also increased steadily during this time.

With increasing activity in the harbor, it soon became clear that the width and depth of the port would have to be expanded. In 1830 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers surveyed Baltimore Harbor and established the central depth at 17 feet. While the harbor had been dredged up until this point, it was the River and Harbor Act of 1852 that authorized “dredging to obtain specific dimensions.” This allowed for a channel to be dredged 22 feet deep and 150 feet wide from Fort McHenry to Swan Point. Brewerton Channel was created in 1869 in order to decrease sediment accumulations and reduce the need for future dredging. As the port continued to grow, new channels were created as needed.

Today, the main channel measures 51 feet deep and 700 feet across. In 2001 Brewerton Channel was expanded to 50 feet deep and 700 feet across. On June 1, 2006, in celebration of the Port’s 300th anniversary, the Governor named the state’s public marine terminals the “Helen Delich Bentley Port of Baltimore.” By mid-2015, the access channel to the Seagirt Terminal was widened to accommodate the world’s largest container ships. And with the expansion complete on the Panama Canal, it is only a matter of time before Baltimore begins to see even more ships. Baltimore is only one of three East Coast ports that can handle the new “mega ships” that will be traversing the canal.