The shores of the Chesapeake Bay and Susquehanna River have long attracted Native American groups to the rich abundance of food and resources. When English explorer Captain John Smith set out to map the Bay in 1608, he documented hundreds of Native American communities.

Many Native American artifacts were biodegradable, being made of wood, bone, or leather, and did not survive the test of time. However, they did leave their mark in something more permanent—stone. Petroglyphs, ancient rock carvings, are found in two areas of the lower Susquehanna.

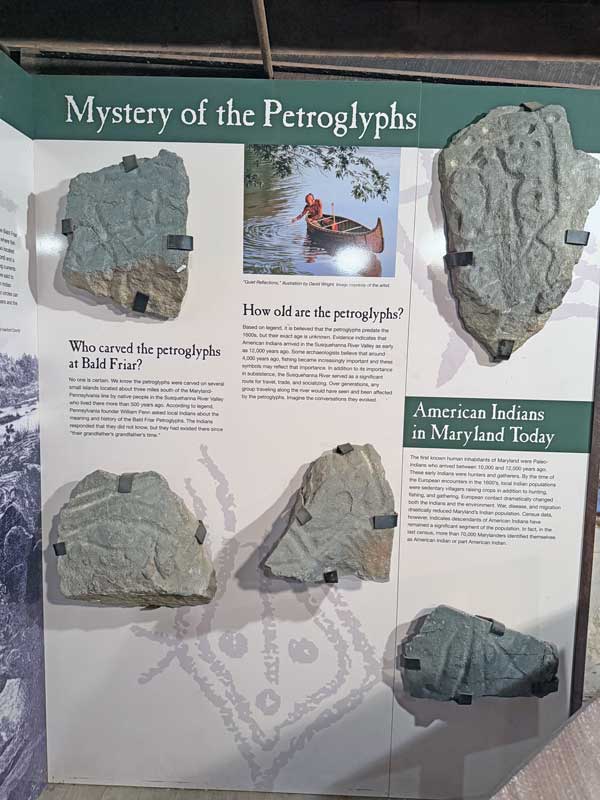

Now inundated by the waters of the Conowingo Basin, the largest concentration of petroglyphs in Maryland was at the Bald Friar site, named for the nearby Bald Friar Falls. It was in the Susquehanna River, three miles south of the Maryland/Pennsylvania border. The site consisted of several small islands, the largest being Indian Rock or Bald Friar Island.

While the exact age of the site is unknown, it is thought to be up to 1000 years old. When asked the age of the carvings by William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania, the local Native Americans were said to have responded that the carvings had been there “since our grandfather’s grandfather’s time.”

The carvings remained relatively forgotten until the 1920s when the impending construction of the Conowingo Dam threatened the destruction of the site. In an effort to save the petroglyphs, a team from the Maryland Academy of Science used dynamite to extricate the carvings. Ninety fragments were recovered and displayed outside the Academy of Sciences in Baltimore. Eventually the stones were moved to Druid Hill Park in Baltimore, the public library in Elkton, and the Harford County courthouse in Bel Air.

The Bald Friar petroglyphs include simple geometric designs, concentric circles, parallel lines, cupping (indentures), and a radiating sun. The most striking and enigmatic motifs are what appear to be stylized faces or heads. There has been conjecture that they represent serpent heads, fish heads, human heads, anthropomorphic fish/human heads, or possibly Iroquois “false face” masks or Delaware “bushy-head” cornhusk masks.

In 2017, a survey was conducted, resulting in 197 of the 226 petroglyphs from Bald Friar being recovered and sent to the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory where they were cleaned, documented, and photographed.

Some of the Bald Friar petroglyphs have been returned to the Susquehanna River near their place of origin. They are now part of an educational display in Susquehanna State Park’s Rock Run Grist Mill in Harve de Grace. Unfortunately, the mill is in need of renovation and is currently closed to the public.

While the Bald Friar petroglyphs were the closest to the Chesapeake Bay, 20 miles upstream, one of the largest concentrations of petroglyphs on the East Coast is located at Safe Harbor in Lancaster County in Conestoga, PA. Located on appropriately named islands, Big Indian Rock and Little Indian Rock, they are accessible only by water.

Located downstream from the Safe Harbor hydroelectric dam, the islands may be reached in two ways. Powered vessels may be put in at the Pequea boat ramp and travel approximately two miles upstream. Canoes and kayaks may launch in the Conestoga River at Safe Harbor Park and paddle approximately a half-mile downstream, entering the Susquehanna River below the dam. Water levels may vary and flashing lights and sirens from the dam indicate an impending water release that could create dangerous conditions.

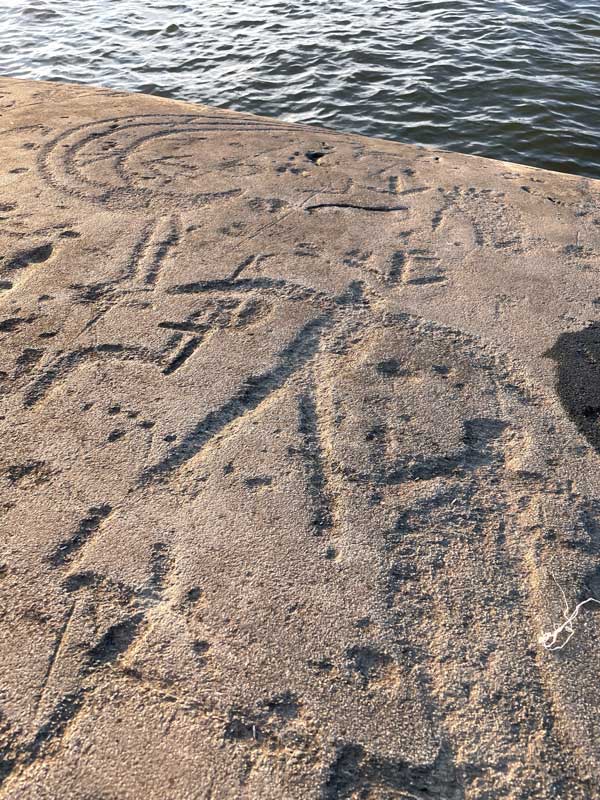

Big Indian Rock is distinguishable from the dozens of other islands due to its large size, relative lack of vegetation, and smooth downward sloping surface. Approaching from the downstream side, there is a relatively flat area suitable for landing.

Depending on your time of arrival, the petroglyphs can be deceptively hard to see. Best viewing times are near sunrise or sunset as the sun’s slanted rays highlight the edges of the carvings. Visibility can be enhanced by pouring water directly into the carvings or by gently stamping around their edges with a wet sponge.

The Safe Harbor petroglyphs are thought to be as many as 1000 years old, created by Algonquian Indians known as the Shenk’s Ferry People, who lived in the area.

Big Indian Rock features various anthropomorphic figures, what has been interpreted as a shaman with a feathered headdress, and an Eagleman. A large noncontemporary carving of a dove resembling Pennsylvania Dutch Fraktur folk art adorns the top of the island.

Farther upstream is Little Indian Rock. It can be identified by carvings of a walking bird, four-legged animals, and a human figure holding a bow on the upriver side of the island. Getting atop the island can be a bit difficult, but the sheer number and variety of petroglyphs makes it worthwhile.

Carvings include animal, thunderbird, and human figures. There are also life-size tracks of birds, bear, deer, and elk alongside a human footprint. The focal point is a Manitou spirit, a god-like being with horns, a beak, and long sweeping curves. Equally impressive are parallel wavy lines that mark the position of sunrise on the spring and fall equinoxes and a “serpent” line, resembling a snake, that corresponds with sunrise on the winter solstice and sunset on the summer solstice.

The Safe Harbor petroglyphs are very different from the Bald Friar carvings. This could indicate that they were made by different cultural groups or had been made at different time periods. Regardless, the sites of the petroglyphs must have held great significance.

Experiencing the petroglyphs firsthand evokes a sense of wonder and a multitude of questions. Why did the Native Americans spend so much time and effort creating the rock art?

Did the carvings serve as a calendar, directional marker, teaching tool, or religious icon? Or was it a combination of all these things and a way for them to have made sense of their world? Perhaps in time, we will be able to glean their meaning and understand these stories in stone.

By Bart A. Stump, Photos by Jennifer Stump