So, you want to be a Captain? Getting your captain's license is a worthy enough goal, but do you know why you want it? Most of those who want a license already know why they want or need it. Perhaps you want to run a fishing charter boat of your own, or give sightseeing tours on the Potomac, or you are applying for a job that requires you to have a license as a condition of employment; all are excellent reasons.

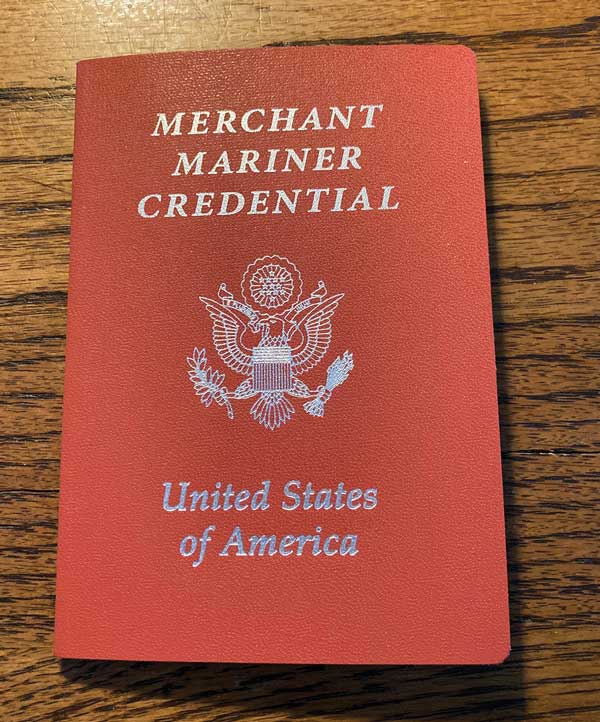

Captain’s licenses are issued by the U.S. Coast Guard, and are properly referred to as a Merchant Mariner Credential, or MMC. An MMC is not just issued for captains; any type of merchant mariner, from AB (deckhand) to Oiler to Mate, may have an MMC. Also, there are more than one type and grade of Captain’s license, so it’s handy to simply refer to it as an MMC. Licenses are valid for five years, then must be renewed, and they are assigned by the Coast Guard in accordance to the vessel tonnage that you are expected to operate. The most common designation is 100 ton, or 100 GRT (Gross Registered Tonnage).

When I first told my wife Denise that I was going to get my Captain’s license, she smirked and replied, “Well, you’re not going to be the Captain of the Love Boat. You know that, right?”

Well, I more or less knew that, but why, you might ask, did I pursue my license? In my case, I had been boating on New England waters practically all of my life and had done a hitch in the Coast Guard many years before. Now, it was around 2008, and our country’s economy was in a bit of a downturn, and business was slow. A captain friend suggested that I might benefit from getting my own license as a way of finding additional employment and making some extra money on the side.

Many licensed captains began simply as owners of their own sportfishing boat, such as a center console model, taking family and friends out fishing on the weekend simply because it’s much more fun to fish with others than to fish alone. That could be you, of course. Then someone suggests that you could make money to pay for your gas by taking paying passengers out for day fishing trips, and before you know it, you’re in the captain’s classroom. This is, in part, due to the fact that in order to take paying passengers out on the water for whatever reason, you must have a license (MMC).

But before charging ahead full throttle, you might want to consider that there are hurdles to jump before you get your license; that’s why it is good to understand the process and to plan ahead. A 100-ton license really is a working license; you are going to use it to make money. Regardless of what you do with it, the amount that you will earn can vary widely.

Plenty of folks who want to obtain a Captain’s MMC begin the effort harboring a number of misconceptions, so it’s good to clear them up ahead of time.

Capt. Art Pine of the Chesapeake Bay Professional Captains’ Association (CAPCA), writes that “The first and possibly biggest hurdle is to amass the required small-vessel sea-service time. To qualify for a license, you need to have logged 360 days on the water in the operation of vessels—with a minimum of four hours each day—at least 90 of which must have occurred during the past three years. You have to present a record of each qualifying day to include on the appropriate form in your application. And you’ll need the signatures of the owner(s) of all those boats to attest to your presence during those times. (If you own the boat, you can attest to your sea-experience yourself.) You’ll also have to pass a few written exams proving that you’re familiar with the rules of the road, coastal navigation, and deck safety; the tests must be proctored by the nearest Coast Guard Regional Exam Center, or you can take a Coast Guard-approved course that is authorized to administer the license exams.”

I attended weeks of classes at Massachusetts Maritime Academy and had a lot of ‘sea-time’ that I could prove in order to qualify for my MMC. If you own a boat or spend a good amount of time every summer out on the Bay running your own boat or working as a mate aboard one, you can probably document enough time.

The captain’s license ‘grade’ that you get is matched to the size vessel that you have operated in earning your sea time. You don’t automatically get a 100-ton (100 GRT) classification, especially for folks who have operated smaller vessels. You can get what is known as a ‘raise in grade’ after you have earned your initial MMC, but you still need experience on a bigger boat to get a higher-tonnage license. I was initially awarded a 50-ton license because I had operated small boats of my own, none larger than 40 feet, for years. When I wanted a ‘raise in grade’ as it is termed, to 100 GRT, I had to obtain records of my U.S. Coast Guard experience on a 213-foot cutter (decades back). That did the trick, though. No matter how long ago, “Sea time never goes away,” a Coast Guard rep advised me.

Also, you must pass a physical exam including overall health and vision in order to get your MMC. You can download the forms and then your doctor must fill out the paperwork and sign off on them. Make sure ahead of time that your doctor or medical facility is approved to complete and submit these forms. Your blood sugar must be in control, your vision correctable to a certain level, etc. When all of this is complete, you submit all your paperwork to the Coast Guard.

You will be required to pass a drug test administered by an approved clinic in your area. Many occupations from truck driving to working on airplanes require initial and occasional random drug testing, so a drug testing clinic should be easy to find and set up an appointment with. Remember that even if your state has made pot legal, it’s still never OK with the Coast Guard, so if you plan to be a Master for a long time, you can’t use pot or recreational drugs.

Next, you will need to pass a CPR/First Aid course and get a certificate attesting to it. Courses are generally organized by the American Red Cross (ARC) and held locally. You must attend in person with others and practice your skills on a CPR mannequin. The credential is valid for two years. Your license is good for five years, so of course you will need to re-certify your CPR/First Aid certificate every two years. You will also need to obtain a Transportation Worker’s Identification Card, or TWIC, which takes time, biometric testing, and fingerprinting, and has a different expiration date than your license or CPR certificate. Some places such as AAA centers will offer access to TWIC services.

It’s quite a few hoops to jump through, so remember to start the process early. I suggest at least a year before you anticipate needing your license. It takes the Coast Guard time to process your paperwork, review your documented sea time and recommendation letters, take your tests, and anything else.

It’s also very important to recognize that operating a vessel with passengers aboard is a tremendous and serious responsibility. Although it’s not pleasant to say, the captain of any vessel wears the biggest target of all on his or her back in the event of a mishap; for this reason, it is often advisable for a captain to have marine liability insurance. The cost varies, and although it isn’t required to operate a vessel, the more time you spend in the wheelhouse, the more advisable it becomes.

One of the brightest days of your career, no matter what you do normally for a living, will be the day that your MMC arrives in the mail!

About the Author: Capt. Michael L. Martel holds a 100-ton near-coastal master’s license and delivers power and sail vessels when he’s not working on his own boat restoration. He is a lifelong boating and marine industry enthusiast, ex-US Coast Guard seaman, private boat owner and rebuilder, and has sailed offshore as captain and mate on bluewater yacht deliveries to Bermuda and the Caribbean and from Maine to Florida.