Lead author Dr. Keith Bayha was conducting fieldwork and collecting jellyfish off the coast of Delaware (Cape Henlopen) for an outreach exhibit when he noticed something different about the jellyfish nearby. "They were much bigger than anything I had seen previously," said Bayha. With his curiosity piqued, he decided to take some samples back to the lab. Genetic testing revealed these animals were quite different than those found in the nearby Chesapeake Bay and Rehoboth Bay. He began work on these jellyfish with Dr. Patrick Gaffney at the University of Delaware and Dr. Allen Collins from the NOAA National Systematics Laboratory, located at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

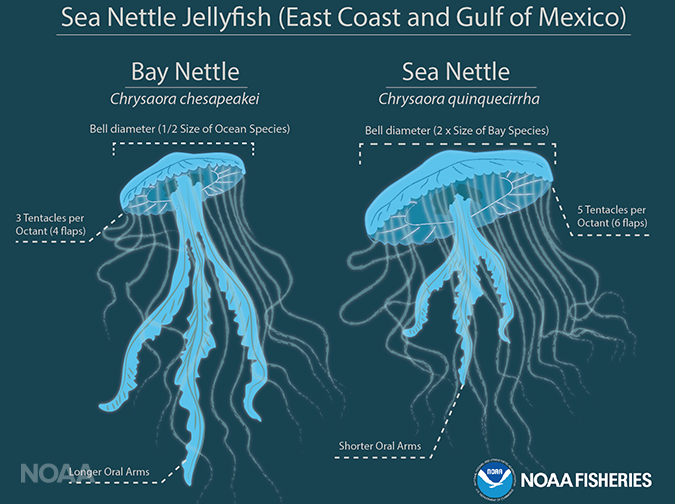

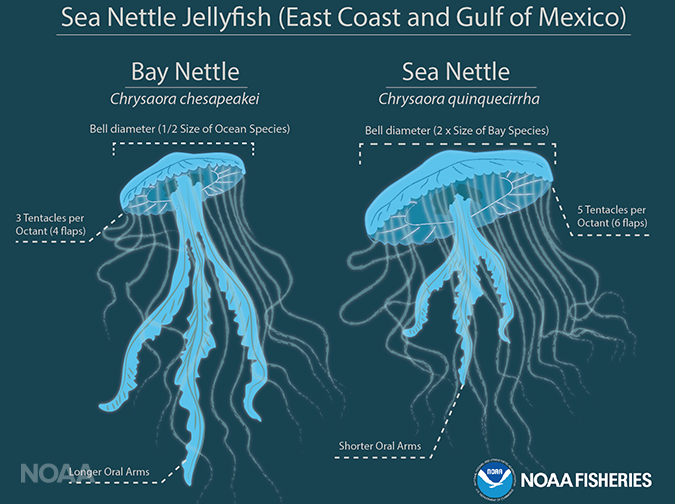

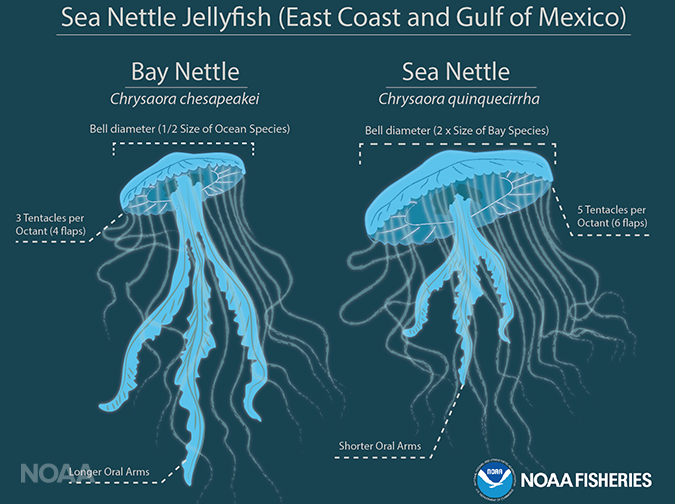

Together they confirmed there were two distinct species–an open ocean-based species (Chrysaora quinquecirrha, "sea nettle") and a Bay-based species (Chrysaora chesapeakei, “bay nettle”). The Bay-based species is found in the less salty waters known as estuaries, such as the Chesapeake Bay, and is the newly recognized species of the two. Both jellyfish were previously called Chrysaora quinquecirrha.

Even more surprising is that this research shows that a jellyfish found in the Chesapeake Bay is more closely related to jellyfish off the coasts of Ireland, Argentina, and Africa than to jellyfish found near Ocean City, Maryland just miles away.

The ocean-based species appears much larger than its Bay cousin. Its bell (the rounded top portion of the species) is almost two times as large as the Bay-based species. It also has more tentacles (40 compared to 24, although some variation exists).

It may be surprising that no one figured out there were two species earlier. As Bayha comments "It's not that I did anything that different, it's just that no one else looked for a very long time. Jellyfish are something people don't pay attention to because they're fleeting. They come and go, are difficult to study, and they don't have hard parts [like] shells that wash up on the shore."

The identification of a new sea nettle jellyfish adds to the roughly 200 species of true jellyfishes worldwide. "To manage a species you have to first know what it is, and we still have a way to go for jellyfishes and other marine species," says NOAA collaborator Allen Collins. For more on this story, click to NOAA.

Lead author Dr. Keith Bayha was conducting fieldwork and collecting jellyfish off the coast of Delaware (Cape Henlopen) for an outreach exhibit when he noticed something different about the jellyfish nearby. "They were much bigger than anything I had seen previously," said Bayha. With his curiosity piqued, he decided to take some samples back to the lab. Genetic testing revealed these animals were quite different than those found in the nearby Chesapeake Bay and Rehoboth Bay. He began work on these jellyfish with Dr. Patrick Gaffney at the University of Delaware and Dr. Allen Collins from the NOAA National Systematics Laboratory, located at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Together they confirmed there were two distinct species–an open ocean-based species (Chrysaora quinquecirrha, "sea nettle") and a Bay-based species (Chrysaora chesapeakei, “bay nettle”). The Bay-based species is found in the less salty waters known as estuaries, such as the Chesapeake Bay, and is the newly recognized species of the two. Both jellyfish were previously called Chrysaora quinquecirrha.

Even more surprising is that this research shows that a jellyfish found in the Chesapeake Bay is more closely related to jellyfish off the coasts of Ireland, Argentina, and Africa than to jellyfish found near Ocean City, Maryland just miles away.

The ocean-based species appears much larger than its Bay cousin. Its bell (the rounded top portion of the species) is almost two times as large as the Bay-based species. It also has more tentacles (40 compared to 24, although some variation exists).

It may be surprising that no one figured out there were two species earlier. As Bayha comments "It's not that I did anything that different, it's just that no one else looked for a very long time. Jellyfish are something people don't pay attention to because they're fleeting. They come and go, are difficult to study, and they don't have hard parts [like] shells that wash up on the shore."

The identification of a new sea nettle jellyfish adds to the roughly 200 species of true jellyfishes worldwide. "To manage a species you have to first know what it is, and we still have a way to go for jellyfishes and other marine species," says NOAA collaborator Allen Collins. For more on this story, click to NOAA.

Friday, November 10, 2017 - 16:04

In mid-October, NOAA reported a new discovery; that one of the most common and well-studied jellyfish species along the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico is actually made up of two species. The sea nettle jellyfish is well-known to beachgoers and researchers alike. Chances are, if you've been stung by a jellyfish in the Chesapeake Bay, it was by a sea nettle jellyfish. For the last 175 years, scientists assumed there was only a single species. But a new paper published in the journal PeerJ finds that what once was thought to be a single species of jellyfish in some of the nation's most popular waterways is actually made up of two distantly-related species.

Lead author Dr. Keith Bayha was conducting fieldwork and collecting jellyfish off the coast of Delaware (Cape Henlopen) for an outreach exhibit when he noticed something different about the jellyfish nearby. "They were much bigger than anything I had seen previously," said Bayha. With his curiosity piqued, he decided to take some samples back to the lab. Genetic testing revealed these animals were quite different than those found in the nearby Chesapeake Bay and Rehoboth Bay. He began work on these jellyfish with Dr. Patrick Gaffney at the University of Delaware and Dr. Allen Collins from the NOAA National Systematics Laboratory, located at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Together they confirmed there were two distinct species–an open ocean-based species (Chrysaora quinquecirrha, "sea nettle") and a Bay-based species (Chrysaora chesapeakei, “bay nettle”). The Bay-based species is found in the less salty waters known as estuaries, such as the Chesapeake Bay, and is the newly recognized species of the two. Both jellyfish were previously called Chrysaora quinquecirrha.

Even more surprising is that this research shows that a jellyfish found in the Chesapeake Bay is more closely related to jellyfish off the coasts of Ireland, Argentina, and Africa than to jellyfish found near Ocean City, Maryland just miles away.

The ocean-based species appears much larger than its Bay cousin. Its bell (the rounded top portion of the species) is almost two times as large as the Bay-based species. It also has more tentacles (40 compared to 24, although some variation exists).

It may be surprising that no one figured out there were two species earlier. As Bayha comments "It's not that I did anything that different, it's just that no one else looked for a very long time. Jellyfish are something people don't pay attention to because they're fleeting. They come and go, are difficult to study, and they don't have hard parts [like] shells that wash up on the shore."

The identification of a new sea nettle jellyfish adds to the roughly 200 species of true jellyfishes worldwide. "To manage a species you have to first know what it is, and we still have a way to go for jellyfishes and other marine species," says NOAA collaborator Allen Collins. For more on this story, click to NOAA.

Lead author Dr. Keith Bayha was conducting fieldwork and collecting jellyfish off the coast of Delaware (Cape Henlopen) for an outreach exhibit when he noticed something different about the jellyfish nearby. "They were much bigger than anything I had seen previously," said Bayha. With his curiosity piqued, he decided to take some samples back to the lab. Genetic testing revealed these animals were quite different than those found in the nearby Chesapeake Bay and Rehoboth Bay. He began work on these jellyfish with Dr. Patrick Gaffney at the University of Delaware and Dr. Allen Collins from the NOAA National Systematics Laboratory, located at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Together they confirmed there were two distinct species–an open ocean-based species (Chrysaora quinquecirrha, "sea nettle") and a Bay-based species (Chrysaora chesapeakei, “bay nettle”). The Bay-based species is found in the less salty waters known as estuaries, such as the Chesapeake Bay, and is the newly recognized species of the two. Both jellyfish were previously called Chrysaora quinquecirrha.

Even more surprising is that this research shows that a jellyfish found in the Chesapeake Bay is more closely related to jellyfish off the coasts of Ireland, Argentina, and Africa than to jellyfish found near Ocean City, Maryland just miles away.

The ocean-based species appears much larger than its Bay cousin. Its bell (the rounded top portion of the species) is almost two times as large as the Bay-based species. It also has more tentacles (40 compared to 24, although some variation exists).

It may be surprising that no one figured out there were two species earlier. As Bayha comments "It's not that I did anything that different, it's just that no one else looked for a very long time. Jellyfish are something people don't pay attention to because they're fleeting. They come and go, are difficult to study, and they don't have hard parts [like] shells that wash up on the shore."

The identification of a new sea nettle jellyfish adds to the roughly 200 species of true jellyfishes worldwide. "To manage a species you have to first know what it is, and we still have a way to go for jellyfishes and other marine species," says NOAA collaborator Allen Collins. For more on this story, click to NOAA.

Lead author Dr. Keith Bayha was conducting fieldwork and collecting jellyfish off the coast of Delaware (Cape Henlopen) for an outreach exhibit when he noticed something different about the jellyfish nearby. "They were much bigger than anything I had seen previously," said Bayha. With his curiosity piqued, he decided to take some samples back to the lab. Genetic testing revealed these animals were quite different than those found in the nearby Chesapeake Bay and Rehoboth Bay. He began work on these jellyfish with Dr. Patrick Gaffney at the University of Delaware and Dr. Allen Collins from the NOAA National Systematics Laboratory, located at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Together they confirmed there were two distinct species–an open ocean-based species (Chrysaora quinquecirrha, "sea nettle") and a Bay-based species (Chrysaora chesapeakei, “bay nettle”). The Bay-based species is found in the less salty waters known as estuaries, such as the Chesapeake Bay, and is the newly recognized species of the two. Both jellyfish were previously called Chrysaora quinquecirrha.

Even more surprising is that this research shows that a jellyfish found in the Chesapeake Bay is more closely related to jellyfish off the coasts of Ireland, Argentina, and Africa than to jellyfish found near Ocean City, Maryland just miles away.

The ocean-based species appears much larger than its Bay cousin. Its bell (the rounded top portion of the species) is almost two times as large as the Bay-based species. It also has more tentacles (40 compared to 24, although some variation exists).

It may be surprising that no one figured out there were two species earlier. As Bayha comments "It's not that I did anything that different, it's just that no one else looked for a very long time. Jellyfish are something people don't pay attention to because they're fleeting. They come and go, are difficult to study, and they don't have hard parts [like] shells that wash up on the shore."

The identification of a new sea nettle jellyfish adds to the roughly 200 species of true jellyfishes worldwide. "To manage a species you have to first know what it is, and we still have a way to go for jellyfishes and other marine species," says NOAA collaborator Allen Collins. For more on this story, click to NOAA.

Lead author Dr. Keith Bayha was conducting fieldwork and collecting jellyfish off the coast of Delaware (Cape Henlopen) for an outreach exhibit when he noticed something different about the jellyfish nearby. "They were much bigger than anything I had seen previously," said Bayha. With his curiosity piqued, he decided to take some samples back to the lab. Genetic testing revealed these animals were quite different than those found in the nearby Chesapeake Bay and Rehoboth Bay. He began work on these jellyfish with Dr. Patrick Gaffney at the University of Delaware and Dr. Allen Collins from the NOAA National Systematics Laboratory, located at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Together they confirmed there were two distinct species–an open ocean-based species (Chrysaora quinquecirrha, "sea nettle") and a Bay-based species (Chrysaora chesapeakei, “bay nettle”). The Bay-based species is found in the less salty waters known as estuaries, such as the Chesapeake Bay, and is the newly recognized species of the two. Both jellyfish were previously called Chrysaora quinquecirrha.

Even more surprising is that this research shows that a jellyfish found in the Chesapeake Bay is more closely related to jellyfish off the coasts of Ireland, Argentina, and Africa than to jellyfish found near Ocean City, Maryland just miles away.

The ocean-based species appears much larger than its Bay cousin. Its bell (the rounded top portion of the species) is almost two times as large as the Bay-based species. It also has more tentacles (40 compared to 24, although some variation exists).

It may be surprising that no one figured out there were two species earlier. As Bayha comments "It's not that I did anything that different, it's just that no one else looked for a very long time. Jellyfish are something people don't pay attention to because they're fleeting. They come and go, are difficult to study, and they don't have hard parts [like] shells that wash up on the shore."

The identification of a new sea nettle jellyfish adds to the roughly 200 species of true jellyfishes worldwide. "To manage a species you have to first know what it is, and we still have a way to go for jellyfishes and other marine species," says NOAA collaborator Allen Collins. For more on this story, click to NOAA.