The Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail follows the route undertaken by members of the Jamestown colony throughout the Chesapeake Bay in 1608. In part one of this three-part series, the author covers an overview of the trail and exploring it by boat.

Captain John Smith got his commission on a battlefield, not an ocean, but he deserves to go down in history as an epic small-boat explorer. During his time on the Chesapeake in the employ of the Virginia Company of London, from April 1607 to October 1609, he and his crew covered 3000 miles around the Bay in a shallop, a 30-foot open boat, operating year-round in everything from stifling heat and sudden thunderstorms to icy cold and blowing snow.

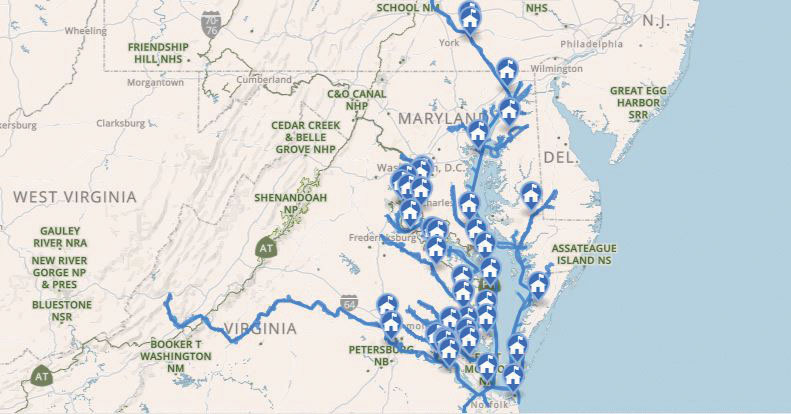

Where did he go? He traveled every major river system on both sides of the Bay except Maryland’s Choptank River, Eastern Bay, and Chester River.

His goals were to strike gold and silver, assess the military strength and trading potential of the Native tribes, find the mythical Northwest Passage through Virginia to the Pacific (which the English at that time were sure existed), and explore and map the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

Though he wasn’t successful on the first and third objectives, he did succeed in making extensive contact with American Indian tribes. He also laid the groundwork for European settlement and commercialization of other resources of the New World.

Mapping the Way

Captain John Smith’s most lasting achievement was mapping the Chesapeake and its rivers. He did so with astonishing accuracy, given his relatively simple but ingenious tools—a compass that doubled as a sundial, a quadrant for measuring latitude, a chip log to measure vessel speed, a traverse board to record distance covered during each four-hour watch, and a notebook. His extensive notes allowed him to publish the first accurate map of the Bay and its rivers in Oxford, England in 1612.

This map became the essential “cruise guide” for English settlement of the Virginia and Maryland colonies in the 17th century. It laid a major foundation for the development of our country in the following century.

An All-Water National Historic Trail

Captain Smith’s Trail was the brainchild of Patrick F. Noonan, then-chairman emeritus of The Conservation Fund. As planning began at the turn of the last century for the Jamestown 2007 commemoration, he mused that, “This isn’t just a Jamestown Thing, or even just a Virginia Thing. It’s a Chesapeake Thing.” He reasoned that because Captain John Smith’s explorations of the Chesapeake and the extraordinarily accurate map he published shortly after played central roles in the development of the Virginia and Maryland colonies, designation of a National Historic Trail following those explorations would bring valuable attention to the Chesapeake and efforts to restore its health.

Noonan was, and is, a very persuasive leader. He quickly drew together valuable partners in the conservation community, beginning with The Conservation Fund, the National Geographic Society, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, and, of course, the National Park Service. Sure enough, his vision came to life as then-President George W. Bush signed our country’s first all-water National Historic Trail into law on December 19, 2006, the 400th anniversary of the day the three Virginia Company ships left Plymouth, England for the New World and what would become Jamestown.

In addition to Smith’s explorations, the trail focuses on the American Indian tribes the English encountered and their history, plus the ecosystem of the Chesapeake Bay and its rivers, then and now.

It’s important to recognize the contributions the Chesapeake Indians have made—and continue to make today—to the history and culture of the region. We must also understand how ecological systems of the rich, diverse Chesapeake in Smith’s day “worked.” Knowledge of them gives us insights that help us continue to restore the health of the Bay ecosystem going forward in the 21st century.

The Trail Today

“Is it open yet?” people sometimes ask. Most definitely. The Chesapeake and its tributary waters are and have been open to everyone for millennia. However, the concept of such a long, extensive all-water trail is not easy to grasp. There’s no acquisition or ownership of territory involved. Instead, the National Park Service and its partners have been busy building a National Historic (Water) Trail “infrastructure” of maps, books, websites, data-gathering buoys, signs, exhibits, and other guideposts to help 21st century boaters explore Captain John Smith’s Chesapeake Trail. Two key parts of this infrastructure are the National Park Service’s Chesapeake Bay Gateways Network and the Chesapeake Bay Interpretive Buoy System of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

What’s even more important is that this National Historic Trail and what we learn from it about Captain Smith’s time on the Chesapeake gives us a well-documented two-year snapshot of the Bay and its rivers. It becomes a vantage point from which to reflect on the centuries that came before it, especially the 400-year era of the Late-Woodland Algonquian Indians that settled around the Chesapeake, and forward through the 400-plus years of history that have unrolled since. That’s a most valuable point of view from which to think deeply about how we humans can most productively live with and care for the Chesapeake and its rivers going forward.

Exploring in Captain John Smith’s Wake

“Are we there yet?” Yes. Remember that your destination is Captain Smith’s Chesapeake Trail itself, all of its 1800 miles of tidal water that by definition is open to the public (with a few military and national defense exceptions that are noted on nautical charts). Whatever kind of boat you’re cruising aboard, whatever section you’re passing through during any given day, you’re following the wake of Captain John Smith and his crew on waters they explored and mapped. You’ll experience the excitement of discovering new-to-you Chesapeake waters, learn to see well-known sites with new eyes, and reflect upon all that the Chesapeake has meant to our country over the past four centuries and what it gives us today.

As you travel the trail, you’ll find places that still look as they did in Smith’s time, but you’ll also see areas where our human footprint weighs heavily on the land and water. We hope you’ll learn about the Chesapeake that Captain John Smith saw—the rich ecosystem that developed naturally without our heavy recent footprint. Once you do, please get involved in restoring its health, for both yourself and future generations of Bay lovers. Contact these organizations to learn more:

- Chesapeake Bay Program Partnership

- Chesapeake Bay Foundation

- Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

- Waterkeepers Chesapeake

- James River Association

- Elizabeth River Project

- Lynnhaven River Now

- Friends of the Rappahannock

- Shore Rivers

- Sultana Education Foundation

- Nanticoke Watershed Alliance

- Arundel Rivers Federation

- Severn River Association

Boating the Trail

The Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail lends itself to a wide variety of boats, from paddlecraft (canoes, standup paddleboards, and kayaks) and 14- to 20-foot outboard skiffs to cruising sailboats, 60-foot trawlers, and every sort of vessel in between. When deciding how to explore the trail, consider the nature of the Chesapeake and Captain Smith’s choice of vessel for his own travels.

A Bay Where the Rivers Are the Roads

The Chesapeake is the “drowned” valley of the Susquehanna River, flooded by tidal water as the sea level began rising at the end of the last ice age, about 15,000 years ago. Unlike other East Coast rivers such as the Delaware and the Hudson, the Susquehanna has a number of large tributaries entering its lower reaches. They too have flooded, creating a sprawling complex of navigable waterways that served as instant infrastructure for a land without roads.

In general, these rivers carry plenty of depth for pleasure craft all the way to their heads of navigation, where their beds meet sea level, but they curve downstream of that point through large and looping meander bends before broadening out as they flow toward the open Chesapeake. River winds become both friend and enemy, depending on which way you’re traveling, as wooded banks channel them directly up or downstream. Meanwhile, flood and ebb tidal currents on most of the rivers actually become stronger upstream. Wind and current running together are delightful for all boats, but when they clash, they can produce nasty, short waves that test any small craft.

Mariners have dealt with these conditions for centuries, whether carrying raw materials like tobacco, timber, and produce downstream or bringing manufactured goods to upriver ports like Richmond on the James River, Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock, Alexandria on the Potomac, or Havre de Grace on the Susquehanna. Until the late 19th century, they used both sail and non-motorized auxiliary power, especially oars.

Your Boating Challenges

Today, there is still plenty of depth in the Bay and its rivers for all but the largest cruising boats. Issues to consider are your boat’s clearance under bridges (a special problem for cruising sailboats up many rivers), its ability to deal with adverse wind and current, and your own knack for reading meander curves with chart, GPS chartplotter, electronic depth sounder, or leadline, and eyes.

Paddling and Rowing

Canoes, kayaks, and paddleboards are wonderful vessels to see parts of the Trail, with many launch points available. Quiet, slow travel makes it easy to absorb the nature of a waterway; to look and listen. For those with the time and training, extended kayak expeditions are extraordinarily satisfying, but even day trips in rented canoes on waters like Mattaponi Creek at the Patuxent River Park near Upper Marlboro, MD, or Gordon’s Creek at the Chickahominy Riverfront Park just west of Williamsburg, VA, serve the purpose. Many larger cruising boats now carry kayaks and standup paddleboards for exploring the numerous creeks and coves on the trail.

Skiffs and Runabouts

Seaworthy, trailerable center console skiffs and runabouts offer a different experience, taking advantage of the large number of public and commercial launch ramps available around the Bay and its rivers. These boats allow day explorations of 25-30 miles at leisurely cruising speeds of 15-20 mph, with plenty of time left over for poking along at slow speed. Open skiffs of 16-18 feet with outboards and push poles can slip into almost as many places as canoes. Modern four-stroke outboards are good choices for power because of their quietness, especially at low speeds, and their fuel efficiency. As more electric outboard power systems become available, they will become even better choices.

Cruising Sailboats

On open water sections of the trail, cruising sailboats are great vessels for extended trips, especially because they require the same kind of seamanship that Captain John Smith had to exercise. Be ready to deal with bridges and the shoals on the insides of meander curves when exploring the upper sections of rivers like the Rappahannock and the Nanticoke. The scenery will often be stunningly beautiful and the wildlife abundant, but fluky winds will dictate traveling under power much of the time. A rowing/sailing dinghy or a kayak will be useful for short explorations.

Cruising Powerboats and Trawlers

Cruising powerboats are good choices for the water trail, especially if they have bridge clearances of less than 25 feet and propeller shafts protected by keels or skegs. It’s important to pay attention to range and self-sufficiency because marina fuel, shore power, and pump out services can be few and far between upstream on several of the Chesapeake’s most interesting rivers. Trawlers lend themselves particularly well to the trail because they tend to be self-sufficient, their low wakes respect shorelines, and their six- to eight-knot cruising speeds are conducive to enjoying the river. Having a dinghy or a couple of kayaks aboard can add to your exploration enjoyment. As with outboards, it’s a kindness to other trail travelers to run the cleanest engines possible and to be courteous with your wake, whether you’re running an express cruiser with twin gas engines, a workboat-type cruiser with a single diesel, a trawler, or a sailboat under power.

For more information, visit nps.gov/cajo/learn/index.htm. Stay tuned for Part Two, which covers different sections of the Trail, next month!

By John Page Williams