A friend asked me if I might spare a couple of days to provide some coaching and instruction on boating safety to a new boat owner, Joe, an older man who had very little experience operating a motorboat. Joe and his wife Anne, living down on Cape Cod, had just become the proud owners of a gently used 28-foot fiberglass wedge-shaped motorboat, a Sea-Ray or something similar, a vee-hull craft with a powerful six-cylinder inboard gasoline engine. The gentleman had no training to speak of in Rules of the Road, safety, navigation, or the basics of operating his new boat, Anne told me, but he needed to learn. She said that she would feel better if he did. She was going to write the check for his training; the training was to be a birthday present for him. I was pleased to be asked and agreed to help them out. His boat was already in the water at a dock in Falmouth Harbor barely a mile from where they lived.

There were, of course, a few little problems from the start. His boat had a VHF radio, for example, but we discovered that it only operated on Channel 16, the hailing and distress channel. He didn’t realize that one could not use it for regular conversations or to get weather forecasts. So, off we went to a nearby West Marine to purchase a new radio, which I installed for him. Then, we were ready to run our pre-departure checks: run the blowers to vent the bilges, check the oil and hydraulic fluid, all of the necessary things that a skipper should do before leaving the dock. But he snickered and wondered what all the fuss was about.

“You need to do these things every time you head out,” I told him, “Because if the engine quits out there, you can’t just step over the side and walk home. What if the weather turned sour and you were stuck out there?” He seemed unimpressed. Once we were finally ready to head out of the harbor, I told him, “I’m going to be standing by, but I’m going to mostly let you drive the boat so that you can get the experience you need.”

Out onto Vineyard Sound we went; it was a beautiful, sunny summer day with a light breeze and a good many boats operating. Barely a quarter mile out of the harbor, he slowed the boat down to a stop and sat there, watching the other boat traffic. “What’s wrong?” I asked. There were two or three boats crossing in the distance from either side, and, he explained he wanted to see where they were going before venturing further. He didn’t want to risk a collision. “But whoever has right-of-way is determined by the Rules of the Road,” I replied. “You follow the Rules, you don’t need to stop. Boats crossing from the right have right of way, for example. It’s really pretty basic.”

Joe was one of those guys who initially assumed that driving a motorboat is much the same as driving a car except that there are no lanes and no road signs. You can pretty much go wherever you want, as fast as you want, and that’s all there is to it. Start her up and drive, it’s all good. The boat had lifejackets, but he saw no use for them, just something to take up space in a locker.

Joe wanted me to show him how to pilot the boat into a small harbor—appropriately named Little Harbor—to see the Coast Guard cutters at the pier. We were heading over and as we approached, I noted that he paid no attention to the red and green channel markers. “You have to observe them,” I admonished him. “There are rocks in there!” His thinking was that the buoys were essentially colorful motifs that artists design onto nautical dish towels.

I came to understand that the reason for this training was, in part, because he and Anne had been fond of going over to Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard on the people-ferry for years and liked to make day trips there. His new boat would be a great way to come and go as they pleased, but of course he had not thought about docking, anchoring, getting ashore, dealing with weather changes; these were all a bit much. Back in Falmouth Harbor, we were trying to successfully complete some small maneuvers, such as approaching a mooring ball, but Joe couldn’t manage it; he would suddenly ‘freeze up’ in what Anne called ‘panic mode.’ The Oak Bluffs people-ferry, a 100-plus foot steel vessel, went by us on its way out of the harbor.

“You see that?” Joe pointed to the ferry proudly. “That’s OUR boat!”

“No,” I replied, exasperated, “THIS is your boat, and you need to learn how to operate it!” That was the end of the lessons for that day.

Nothing Like Driving a Car

The Covid pandemic convinced a lot of people to become new boat owners and operators, people who had never owned boats before. For many, the mistaken motivation was to go somewhere ‘safe’ from disease and without burdensome restrictions. Many had the idea in their heads that “It’s no different than driving a car.” It is, in fact, absolutely nothing like driving a car except that a motorboat has an engine and a steering wheel. That’s about it. There are so many people in powerful motorboats out on the water who have no idea about what they are doing that it is actually a defensive strategy to take a course in safe powerboat operation and then to be proactive in putting together your own individualized ‘checklist’—like an airplane pilot’s checklist, for example—before leaving the dock each time. Many states now require powerboat operators to have a license, and that’s a very good thing, because it ensures that the license holder has completed some training in Rules of the Road and the basics of safe navigation and operation. A motorboat operating at speed with a clueless, careless, or drunken driver at the helm is just as deadly as an unguided missile.

When it comes to boating safety, a good part of it is covered by rules, and a good part of it is common sense. Rules vary by state, and there are plenty of boating safety courses that a prospective operator can take. Most states offer a free guidebook summarizing laws and safety guidelines for operating powerboats within their jurisdictions. But being safe on the water is in many ways a ‘state of mind’ that one must cultivate for oneself and especially for passengers when you are taking family and friends out in your boat for a day on the water.

Know What You’re Doing and Plan Your Trip

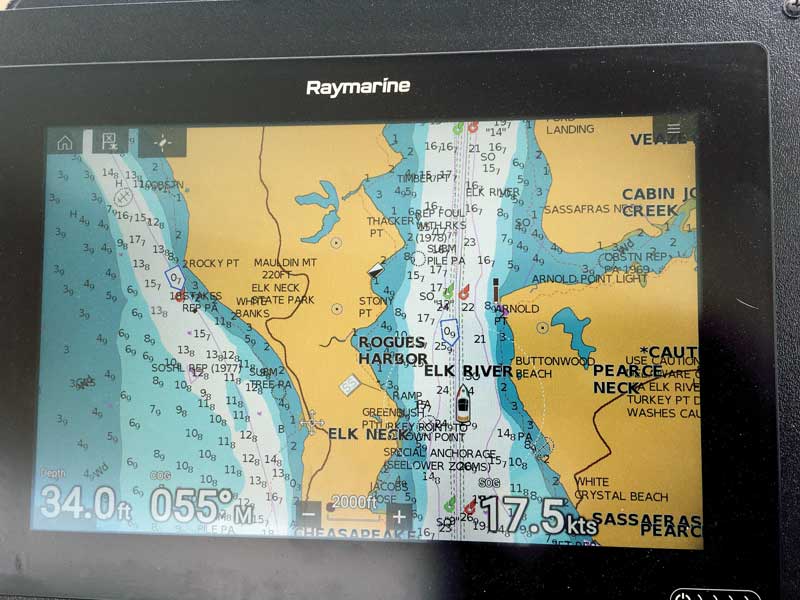

You can jump into your car in your driveway, start it up, and head out onto the road. With a powerboat, the procedure is a bit more complicated. I suppose that the first rule is to know what you’re doing and plan your trip. Get the day’s marine weather forecast before you leave the house. How much wind will you have in your area? Will the weather change? Will there be squally weather or storms? If your trip is going to take you any distance, down a canal or waterway, are there any bridge closures, shoaling, etc. that you should know about? Have you checked out your Local Notice to Mariners from the U.S. Coast Guard? What about charts? My student Joe had no need of charts, and he had never taken the time to learn how to read one anyhow. “I don’t need a chart,” he said, “I know where I am!” He could point out the approximate location of his home street on the paper placemat at the Clam Shack down the street.

Knowing the rules and having the right equipment aboard is not difficult. Planning ahead, however, is everything. “Forewarned is forearmed,” the old proverb goes. And remember to have your own checklist, as pilots do.

Check your engine oil, fluids, fuel, and vent your bilges (gasoline or diesel) first. Always open a hatch and look into the bilge for things that don’t belong there (like water, oil, etc.). Make sure that a friend or relative knows where you are going and when you plan to return; that’s quite simply known as a ‘float plan.’

Bring what you need or even might need. This includes bottled water and a lunch, and you should always have stowed extra quarts of oil, fan belts, and the boat’s own basic tool kit. USCG regulations require that your flares or flare kit and fire extinguishers are up to date, and of course you should have an appropriate lifejacket or PFD for each person aboard. These requirements are real, and you should learn what they are because the Coast Guard is very serious about them. If you are pulled over on the water by the Coast Guard for any operating infraction, a single infraction can quickly become a long list, accompanied by hefty fines.

Planning ahead, and anticipating the unexpected, is key. I’ve seen boats with tiny anchors mounted up on the bow with no line attached, etc. Not only is the anchor probably too small to be effective, but down in a locker there might be barely 50 feet of smelly, coiled rotting line that has never seen the light of day. Guys like Joe consider the bow-mounted anchor much the same as a hood ornament on an old Buick. “Oh, we never use that,” Joe replied, when asked. “What if you needed to deploy it, someday? Would you know how to set it up and use it?” I asked. Joe shrugged and smirked. The same attitude applied to navigation books and Rules of the Road. Joe waved his hand. “Oh, I’ve read books,” he dismissed.

Preparation is crucial before leaving the dock; take the appropriate amount of time, go over your checklist, do it right. Once you start your engine, fire up your electronics and make sure that they work, particularly your chartplotter, and conduct a quick radio check on a common channel for your area, such as VHF Channel 68. Is your area prone to fog? Then your boat should be equipped with radar, or at the very least a loud horn. Signaling devices are not only critical but a requirement. A radio is not a substitute. Know how to use a coastal chart to plan your trip and be aware of the basic Rules of the Road to avoid the possibility of collisions. Lastly, and very importantly, make sure that your navigation lights are all working. Many a trip that was planned for the day ends up lasting well after sundown. Remember also that a mobile phone is not a substitute for a VHF radio. A radio has a greater range and also reaches the people you might need to reach. You can’t broadcast a mayday call on your iPhone.

Boating safety and having a good trip out on the water versus a disaster is all about planning and preparation, knowledge, the right attitude, and maintaining constant situational awareness of your surroundings; this includes other vessels nearby, changing weather and sea state, and knowing where you are at all times.

Be safe and have fun!

About the Author: Capt. Michael L. Martel holds a 100-ton near-coastal Master’s license and delivers power and sail vessels when he’s not working on his own boat restoration. He is a lifelong boating and marine industry enthusiast, ex-US Coast Guard seaman and private boat owner and rebuilder, and has sailed offshore as captain and mate on bluewater yacht deliveries to Bermuda and the Caribbean and from Maine to Florida.