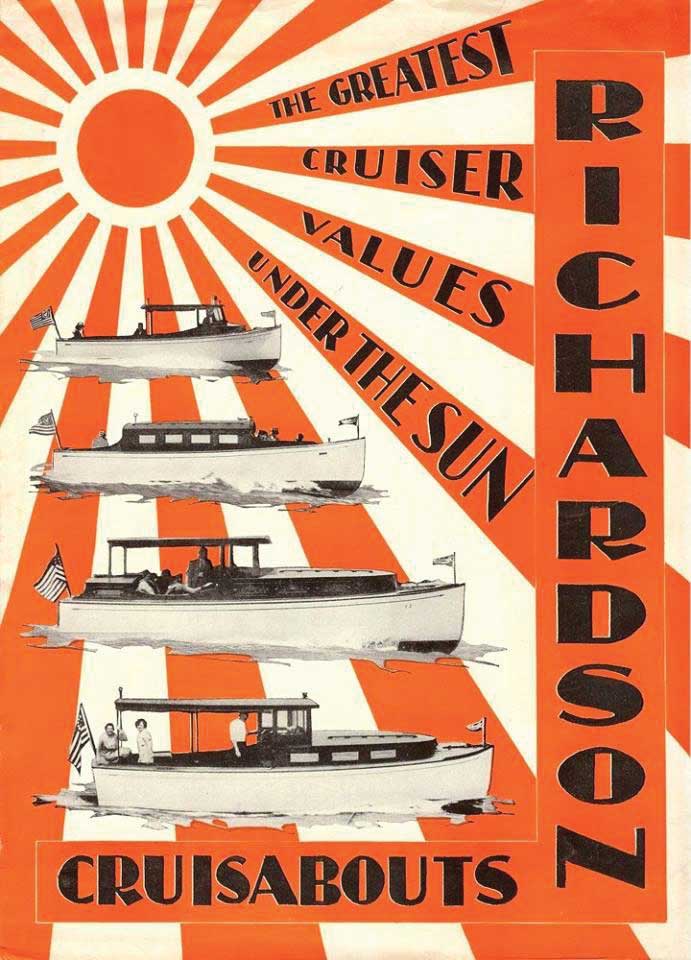

Paul Spadaro is a determined man, grounded by an education in science, yet allured by the romance of boating days gone by. In 1978, he bought a 1929, 30-foot Richardson Cruisabout. New, the boat sold for around $2500, which was a lot of money in those days. Spadaro paid $450 for it, but the old boat was not seaworthy. However, Spadaro’s plan was not to go cruising on it. Instead, he intended to keep the boat on land as a place to live. Back then, he didn’t realize his purchase would turn into a lifelong project.

The aging boat made of cedar planks on oak frames needed a lot of work. The cedar was in good shape, but the oak was badly deteriorated, so much so that the cedar planks were coming off the oak frame. The boat also had a big hole in the bow, which Spadaro patched soon after he bought it. When he finally decided to put the boat in the water, it leaked everywhere. The vessel had serious leaks at the rudder post and from the stuffing box. The transom also needed to be replaced. The new owner named the boat Patches for all the patchwork she needed.

Spadaro’s father and brothers helped with some of the woodwork and got the antique in-line six-cylinder Kermath engine started. The company’s clever slogan was, “a Kermath always runs,” but they went out of business in the 1950s. The old engine sat idle for years. Since parts were nearly impossible to find, Spadaro replaced the Kermath with a Gray’s Marine in-line four-cylinder gasoline engine four years ago.

Formerly of Westchester County, NY, Spadaro graduated from the State University of New York at New Paltz with a bachelor’s degree in geology. He moved to Maryland in 1980 to take a job in Silver Spring with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as an aeronautical cartographer, a map maker for airplane pilots. Spadaro started back when charts were made by hand. He retired in 2014 after 34 years with NOAA. He also taught earth science at the community college level for a time. Currently, Spadaro is president of the Magothy River Association, a non-profit group founded in 1946 dedicated to preserving the river. Much of his time is devoted to MRA-related duties.

When Spadaro moved to Maryland, he brought Patches with him. At first he only worked on the boat a few weeks a year, but after he retired, he had more time for working on Patches. Spadaro is happy to have an inside place to work on the boat at Cypress Creek Marina. For the past few years, marina owner Allen Flinchum and shipwright Drew Kauffman have helped Spadaro, not only with storage space, but also with sage advice. On their recommendation, he rebuilt the hull using a cold molding process, which is essentially building a hull on top of a hull. Spadaro used many sheets of marine grade plywood and gallons of glue for the job. It is a time-consuming process, but after much stripping, sanding, shaping, and swearing, the final plank was installed two years ago.

It is customary to have a sip of whiskey once the last plank is installed. So in 2017, Spadaro and 80 of his closest friends did just that. A fine time was had by all. Since then, the hull has been fiberglassed and sealed. There is no major work left to do on the boat, only cosmetics such as cleaning and painting. The metal needs to be polished.

Spadaro explained, “Older vessels used brass and bronze cleats and fittings. Newer boats are made with chrome and stainless steel which is much easier to clean. Nowadays people don’t want to spend much time polishing the metal on their boats.”

Patches is able to float right now. She needs to be put in the water so that the waterline can be marked, because it has likely changed due to the added weight of the reinforced hull. Then she needs to be pulled to have drains installed and painted. Patches’s hull will be white with a red bottom.

An upholstered bench seat goes across the back, but there is no seat at the helm for the captain. The boat was designed that way, says Spadaro. “That’s when men were men; only a wimp would dare sit!”

The boat’s top speed was about 11 knots when new. Spadaro said, “Today, she will be lucky to go seven knots.”

The Richardson Boat Company went out of business around 1962. By 1978, there were only six known Richardson Cruisabouts remaining in existence. Patches may be the last of her kind and among the older wooden boats on the Bay.

The hard-working owner is working on Patches nearly every day now. The goal is to have her ready for the 32nd Annual Antique & Classic Boat Festival at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels on June 14 and 15. Patches is registered in the Amateur Preservation category. After the show in June, Spadaro plans to use his boat to cruise around the Magothy River, go to restaurants, and enjoy time boating on the Bay. He hopes to see Patches cruise to her 100th birthday in 2029.

By Tim Campbell