Back around the turn of the century, Hoopersville, MD, (on Hoopers Island on Maryland’s Eastern Shore), was the epicenter of the Chesapeake Bay crab world. And it was in this spot in 1890 when Captain John Morgan Clayton (known as "Captain Johnnie") established the J.M. Clayton Company at the end of a 1000-foot wooden pier. Today the J.M. Clayton Company is headquartered in Dorchester County at the seaside town of Cambridge, MD. At 123 years old, it is the oldest continuously run crab processor in the world, processing tens of thousands of pounds of premium crab meat each year.

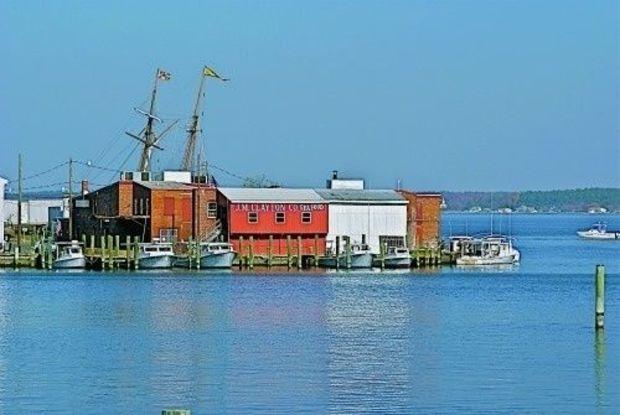

Driving east on U.S. Route 50, you’ll likely miss the J.M. Clayton plant, which is situated along the water on Cambridge Creek, just downstream from the Maryland Avenue drawbridge. It takes a few twists and turns to get there from the busy highway, but once you’re within a couple of hundred feet or so, the unmistakable sweet smell of steaming blue crabs fills the air. The company has been here since 1921, when Captain Johnnie sought better means (rail and steam ferries allowing access to Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City) to transport his sensitive, perishable product. And he didn’t just abandon his experienced crew in Hoopersville, either—he packed all of them up and moved them to Cambridge. The rest is history.

First things first, though. If you want to have any sort of street credentials when it comes to crab meat, you’ll need to be able to speak the lingo and know how crab meat is graded. Generally sold by the pound, you can purchase crab meat fresh, canned and pasteurized, or frozen, which just happens to be sacrilegious. Fresh crab meat usually comes in translucent plastic one-pound containers, pasteurized meat is labeled as such and comes in cans or plastic containers with sealed metal lids, and frozen… well, really? Fresh tastes the best, but pasteurized meat comes in a close second where you trade consistent availability for a bit of that super-fresh taste. Fact of the matter is that once you’ve mixed the meat with crab imperial or crab cake fixings, it’s hard to tell the difference.

Crab meat comes in several different grades. Think of these like you’d think of cuts of beef—each type of meat comes from a different part of the crab. Perhaps the most-prized and best-tasting meat (consider it the filet mignon) is referred to as “Jumbo Lump.” These are the whole, unbroken pieces of sweet, white crabmeat from the swimmer fin cavity of the Chesapeake blue crab—it’s the biggest muscle on this savory crustacean. “Lump” meat contains white meat from the crab with both large and small pieces. “Backfin” is from the small cavities of the crab body, and “Claw,” is the claw meat, of course.

Joe Brooks, the fourth-generation vice president of the company, met us at J.M. Clayton’s Cambridge facility on a swampy, hot June day to show us around his operation and describe the steps taken to make their product among the best you can buy. The process starts at the facility’s loading dock and creek-side wharf where deadrise workboats arrive from the Bay and suppliers from the road unload their catches into large stainless steel cooking baskets. Brooks says, “Maintaining a constant supply of crabs can be a challenge in our business so we work really hard to have great relationships with our crabbers. We always tell them, ‘We will buy all of your crabs if you sell us all of your crabs.’”

Supply can be a challenge in this business with fluctuating crab populations, natural cycles, and other variables. “This season was our slowest start ever,” Brooks says, adding, “And that’s hard when you have a workforce to pay but not enough crabs to pick. Yeah, April and May were tough, but thankfully we’re back up to steam now and operating at capacity.” Today, the crab processing operation generally runs from April through the end of November.

Got a crab jones in the middle of winter? No worries, J.M. Clayton stockpiles a large inventory of pasteurized meat to last through the off-season. After offload, the large stainless baskets are wheeled into the cooking room, which is highlighted by two large stainless steel pressure vessels that can hold about 20 bushels of crabs each and cook them in an astoundingly short time. “I got these from Acme Canning in Hurlock, MD, about 20 years ago,” Brooks says. “The bottoms eventually wear out, so we have to make repairs to them, but that works for us,” Brooks adds. The cookers are fed a supply of highly pressurized steam that raises the temperature in the vessels to 240-250 degrees Fahrenheit. The heat and pressure is the key to cooking big quantities of crabs quickly. The crabs are not seasoned to that only the clean, sweet crab taste comes through in the end product.

About 15 to 20 minutes later, the crabs are removed from the cookers and placed under a high-speed exhaust vent, which pulls much of the steamy heat from the crabs before they are transferred to a refrigerator to chill overnight. Brooks says, “After refrigeration, the crabs pick much better and we also don’t want our pickers to have to mess with hot crabs. It’s a food safety issue, too. Once cooked, we want the crabs down to a proper temperature so the meat is as fresh as possible.”

Getting the meat out of a crab (picking it) is tedious, time-consuming, difficult work, which helps to explain the relative high cost of the meat. The demanding nature of crab-picking work also means that finding and maintaining a consistent workforce that knows how to do the delicate work can be a challenge. Because of the trouble in finding local Eastern Shore labor to pick the crabs, Brooks now relies on the Guest Worker Program, which allows him to bring in workers from Central America for the summer. The workers return to their home countries at the end of the season each year. Brooks says, “Believe me, if we could find local people willing to do the work, we’d hire em’. We are not allowed to displace any American workers with a Guest Worker; if someone qualified applies, we have to make a space for them. The expense is high, though. We pay to fly them up here and have a lot of regulations to follow in regard to hiring and employing them. Overall, though, the program works well for us and we now have many Guest Workers who return year after year.”

After taking a chill overnight in one of J.M. Clayton’s large walk-in refrigeration rooms, workers dump the crabs from the stainless baskets into large wheeled bins that are pushed into J.M. Clayton’s picking room to keep the pickers well-supplied with fresh crabs to pick. When you walk into the large picking room at J.M. Clayton, the first thing that hits you is how cool the area is kept. The second thing that hits you is the cacophony of crunching, snapping, and cutting sounds made by 60 pickers working at full steam. “We keep this room very cool,” Brooks says, adding, “It’s all about freshness and quality of the meat.” The refrigerated crabs are brought into the room sand distributed with shovels onto the long stainless steel tables, which are lined with about 15 pickers each.

The first person who caught my eye among the sea of pickers was a slight woman in a delicate white sweater who was rhythmically rocking as she dissected meat from shell at an alarming pace. “This is Nicey Jones,” Brooks says, “She’s been working for us for 58 years,” to which Nicey quips back, “Fifty eight? I’ve been here 63 years, Joe.” Nicey’s genuine smile and smooth Eastern Shore drawl are charming, and the contrast between her weathered hands and the delicate meat she’s been picking for more than six decades creates a picture that demands pause. “Folks don’t want to do this kind of work anymore,” Nicey says, “It’s been good to me, this work. My niece works here and a lot of my family going back a long time has, too.”

Pickers use crab knives to break down the essential part of crab into four pieces. First, the claws are removed and tossed into a bin for other pickers to separate into claw meat and claw meat “fingers.” The next steps come in a 30-second blur: The shell comes off, the mouth parts come off, and then the gills are removed. The knife makes quick work of the crab’s legs and swimmers next, followed by a cut down the center to split the crab into two parts. The last step is perhaps the most difficult to master. By cutting the two halves in a special way, the jumbo lump easily falls out and the rest of the small compartments are then accessible with the knife. It’s an amazing thing to watch if you’re used to methodically spending hours on the back porch during the summer picking a dozen or so crabs that would take one of these skilled masters only minutes.

One bushel of normal-sized crabs yields about four pounds of crab meat each, and an efficient picker can blast through a bushel an hour. But not so fast, Brooks says. “Part of what we try to do here is to ensure the highest-quality shell-free crab meat out there, so while we like it when our pickers can move through a mess of crabs quickly, we also make sure they’re not going too fast and leaving shell bits in the meat.” Brooks says that it’s all about J.M. Clayton’s emphasis on quality control. “The pickers are supposed to get up every 90 minutes and weight their meat, and then transport it to the packing area. Here, other workers spot check their work and report any shells or other abnormalities on a large whiteboard with the picker’s number on it,” Brooks says.

Pickers are paid by the pound for their work and each proudly marks their number on each can. “If you ever have any compliments or criticisms about our crab meat, just look on the container for a number and give us a call,” Brooks says. “We always want to be producing the best meat available.” J.M. Clayton’s crab meat is available at seafood markets all across Maryland and Virginia, including larger retailers such as Whole Food Markets. If you’ve never tried it before, give J.M. Clayton’s crab meat a try and you’ll surely taste the love that goes into every pound.