This story originally appeared in the December, 2007 issue of PropTalk. Enjoy this Flashback Friday post!

If you’re one of those boaters who’s always falling in love with some classic Chesapeake Bay wooden boat, a

Trumpy, a Bay-built workboat, or even the occasional cedar crab skiff, read this story before you make the commitment.

Unless you’ve salted away stacks of money, buying and restoring a genuine Bay classic is likely to be prohibitively expensive, will occupy all your waking hours for months, and will leave you hard-pressed to make any money out of the venture—even if you plan to charter the vessel out or operate it as a tour boat.

On top of that, you’re apt to remain hopelessly attached to the boat emotionally long after you decide to sell it and move on.

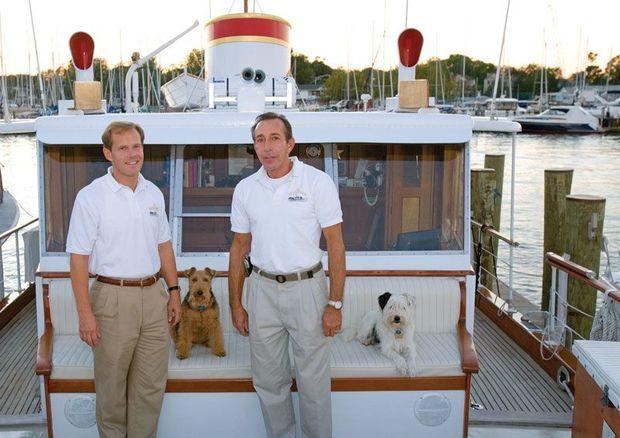

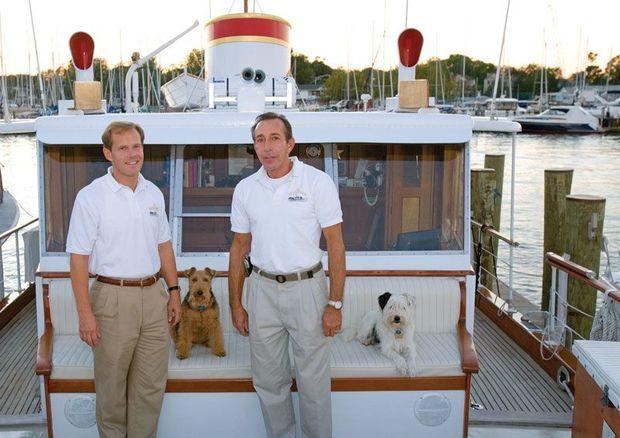

Ask Dan Ramia and Lee DiPaula. By chance, in 2002, the two Annapolis-area classic-boat enthusiasts were invited to lunch aboard the

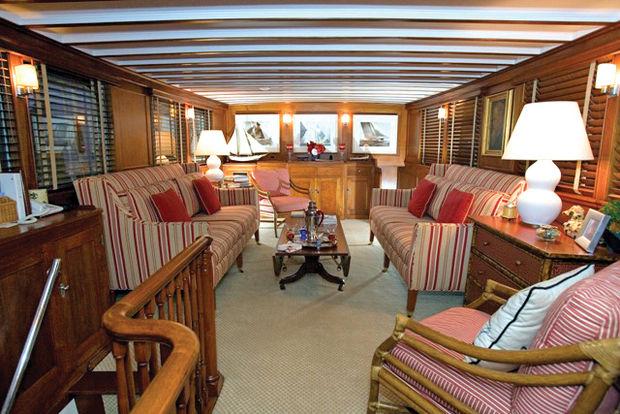

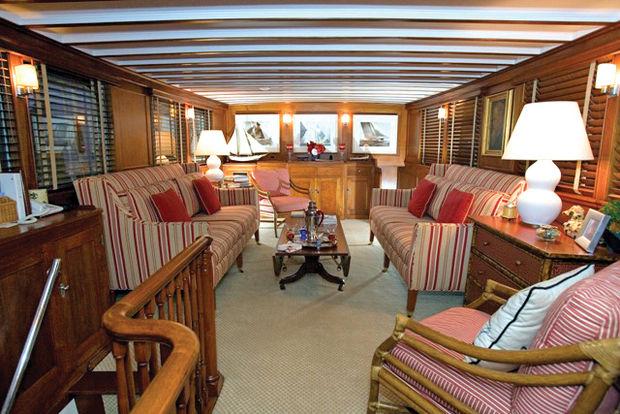

Washingtonian, an aging, all-wooden luxury yacht that had been rescued from disrepair and partially restored. The 61-foot vessel was squat and plumb-stemmed, with three spacious staterooms, a mahogany-trimmed saloon, and plenty of sheltered deck space for guests to stroll. Not everyone’s dream boat—at least at first blush.

But this was no ordinary boat. It was a genuine Trumpy—designed and built in 1939 by John Trumpy & Sons of Gloucester, NJ (1939-47) and Annapolis (1947-71), one of the nation’s oldest and best-known builders. Trumpy had designed the 104-foot

Sequoia, which ultimately became the first presidential yacht, and he was renowned as a boatbuilding craftsman. For most classic-boat buffs, merely boarding a Trumpy vessel is a memorable treat.

By the end of lunch—and a brief-but-idyllic cruise on the Miles River—Ramia was smitten. He rushed home to research the history of the boat and the people who built her online. “To me, this was what boats and yachts are all about,” he says, recalling his reaction. Two years later, Ramia, who had recently earned his Coast Guard captain’s license, was looking around for a classic boat. He’d already begun making inquiries about available Trumpys when the owner of the

Washingtonian, who’d heard about his search, called to offer him a deal that he said “you might not want to refuse.” Teaming up with DiPaula, Ramia snapped it up almost immediately and the adventure began.

DiPaula and Ramia weren’t exactly starting from scratch. The previous owner had told them he’d pumped nearly $1 million over five years into structural repairs, reconfiguring some of the cabins, and updating the electrical and plumbing systems. Still, it was clear there was more to be done.

For openers, the stern leaked, the rudders needed major rework, the hull was covered with barnacles, and the fittings were corroded. On the advice of a marine surveyor, the two decided to replace some of the planking and recaulk the teak deck. They rebuilt the windlass and upgraded the electronics. The living spaces needed redecorating and new furnishings—both the province of DiPaula, 59, who is an interior design consultant and restoration artist. And did we mention having to spruce up much of the old varnish and apply four new coats? “We realized that we’d have to re-do a lot of stuff that was done wrong,” DiPaula says.

One of the first challenges Ramia and DiPaula faced was finding a boatyard that could haul out a vessel that size and had experience working on wooden hulls. Few modern boatyards are willing to handle anything but fiberglass or metal boats. Putting your boat in the hands of a repair shop that’s incompetent or unscrupulous can easily ruin a restoration project. “It’s hard to find people who know how to do that kind of woodworking,” Ramia says.

The new owners finally hauled her at Tidewater Marine in Baltimore and hired two men who had worked for Trumpy in Annapolis to do some of the structural repairs. Ramia and DiPaula performed much of the cosmetic work, painting, and varnishing. “I cashed in a lot of assets, and Lee did, too,” says Ramia, a 49-year-old University of Maryland administrator, who took a six-month sabbatical to work on the

Washingtonian. “We were spending 50-some hours a week fixing her up,” he says. “But rising costs were a continual frustration.”

The restoration went slowly. At the end, the vessel looked every inch the epitome of the luxury yacht of the 1930s with rich mahogany trim, both outside and in, sparkling white paint, and a club-like interior that would make anyone feel at home. Finally, in August 2005, the two men began operating the

Washingtonian as a charterboat. Although the vessel had been Coast Guard-certified to carry up to 34 passengers, the owners limited their cruises to only a handful, hiring a captain to operate the boat and a catering service to provide the food. The business grew slowly as the company set up a website and printed brochures. Mainly, the news spread by word of mouth—a birthday party here and a family of Bay-watchers there. “It’s a limited, specialty market,” Ramia says.

The costs finally overwhelmed them. Ramia estimates that on top of the thousands the two spent to restore the boat, it would take about $100,000 a year to maintain and keep the boat and make further improvements. And that doesn’t include business costs such as advertising and brochures. “It was an eye-popper,” he recalls.

Halfway through the venture, the company suffered a setback when Maryland reaffirmed that it would bill them for excise taxes even though the boat was in the state only six months out of the year. They searched for grants and other sources of money but failed to find them. Finally, last October, they sold the Trumpy to a buyer in St. Augustine, FL, who has been operating it as part of a charter boat business.

Neither man has any regrets. “To be on that vessel would bring on a feeling of being so special and part of an era that doesn’t exist anymore,” Ramia says. “Lee and I were working owners of that boat. We knew how everything operated. It was a matter of great pride to us that we had turned her into the pristine example that she finally was. She was one of the finest-looking Trumpys of that era.” But, he adds, keeping a boat like the

Washingtonian “is going to be a passion, and you have to be able to afford that passion.”

The bond between the boat and its former owners continues. Both Ramia and DiPaula have kept in touch with the new owner, providing an institutional history and even some advice when needed. Ramia still has photos of the Trumpy on the screen-saver on his office computer and has saved the brochures and the inevitable T-shirts from the venture. There are photos of the boat all over his house.

“She’s still very much a love of mine,” Ramia says of the

Washingtonian, “and she’s still very much missed. I would encourage anybody who has a love of the water and fine craftsmanship to go into buying a classic boat, but you need to go into it with your eyes open. I’m thankful for the experience—it’s something I wouldn’t trade for the world. But it’s not an investment; it’s a labor of love. It will cost you triple what you intended.”

Neither Ramia nor DiPaula has given up the love of classic boats. DiPaula has bought a 50-foot Elco cruiser built in 1930 that’s faintly reminiscent of the

Washingtonian and is restoring her with plans to “cruise up to New England for a while.” And Ramia is looking for another classic boat—this time in a “more manageable” range of 35- to 40-feet long.

Now, where were we again?

About the Author

About the Author: Art Pine is a freelance writer, USCG-licensed captain, and a longtime Chesapeake Bay power and sailboater.

Unless you’ve salted away stacks of money, buying and restoring a genuine Bay classic is likely to be prohibitively expensive, will occupy all your waking hours for months, and will leave you hard-pressed to make any money out of the venture—even if you plan to charter the vessel out or operate it as a tour boat.

On top of that, you’re apt to remain hopelessly attached to the boat emotionally long after you decide to sell it and move on.

Ask Dan Ramia and Lee DiPaula. By chance, in 2002, the two Annapolis-area classic-boat enthusiasts were invited to lunch aboard the Washingtonian, an aging, all-wooden luxury yacht that had been rescued from disrepair and partially restored. The 61-foot vessel was squat and plumb-stemmed, with three spacious staterooms, a mahogany-trimmed saloon, and plenty of sheltered deck space for guests to stroll. Not everyone’s dream boat—at least at first blush.

But this was no ordinary boat. It was a genuine Trumpy—designed and built in 1939 by John Trumpy & Sons of Gloucester, NJ (1939-47) and Annapolis (1947-71), one of the nation’s oldest and best-known builders. Trumpy had designed the 104-foot Sequoia, which ultimately became the first presidential yacht, and he was renowned as a boatbuilding craftsman. For most classic-boat buffs, merely boarding a Trumpy vessel is a memorable treat.

Unless you’ve salted away stacks of money, buying and restoring a genuine Bay classic is likely to be prohibitively expensive, will occupy all your waking hours for months, and will leave you hard-pressed to make any money out of the venture—even if you plan to charter the vessel out or operate it as a tour boat.

On top of that, you’re apt to remain hopelessly attached to the boat emotionally long after you decide to sell it and move on.

Ask Dan Ramia and Lee DiPaula. By chance, in 2002, the two Annapolis-area classic-boat enthusiasts were invited to lunch aboard the Washingtonian, an aging, all-wooden luxury yacht that had been rescued from disrepair and partially restored. The 61-foot vessel was squat and plumb-stemmed, with three spacious staterooms, a mahogany-trimmed saloon, and plenty of sheltered deck space for guests to stroll. Not everyone’s dream boat—at least at first blush.

But this was no ordinary boat. It was a genuine Trumpy—designed and built in 1939 by John Trumpy & Sons of Gloucester, NJ (1939-47) and Annapolis (1947-71), one of the nation’s oldest and best-known builders. Trumpy had designed the 104-foot Sequoia, which ultimately became the first presidential yacht, and he was renowned as a boatbuilding craftsman. For most classic-boat buffs, merely boarding a Trumpy vessel is a memorable treat.

By the end of lunch—and a brief-but-idyllic cruise on the Miles River—Ramia was smitten. He rushed home to research the history of the boat and the people who built her online. “To me, this was what boats and yachts are all about,” he says, recalling his reaction. Two years later, Ramia, who had recently earned his Coast Guard captain’s license, was looking around for a classic boat. He’d already begun making inquiries about available Trumpys when the owner of the Washingtonian, who’d heard about his search, called to offer him a deal that he said “you might not want to refuse.” Teaming up with DiPaula, Ramia snapped it up almost immediately and the adventure began.

DiPaula and Ramia weren’t exactly starting from scratch. The previous owner had told them he’d pumped nearly $1 million over five years into structural repairs, reconfiguring some of the cabins, and updating the electrical and plumbing systems. Still, it was clear there was more to be done.

For openers, the stern leaked, the rudders needed major rework, the hull was covered with barnacles, and the fittings were corroded. On the advice of a marine surveyor, the two decided to replace some of the planking and recaulk the teak deck. They rebuilt the windlass and upgraded the electronics. The living spaces needed redecorating and new furnishings—both the province of DiPaula, 59, who is an interior design consultant and restoration artist. And did we mention having to spruce up much of the old varnish and apply four new coats? “We realized that we’d have to re-do a lot of stuff that was done wrong,” DiPaula says.

One of the first challenges Ramia and DiPaula faced was finding a boatyard that could haul out a vessel that size and had experience working on wooden hulls. Few modern boatyards are willing to handle anything but fiberglass or metal boats. Putting your boat in the hands of a repair shop that’s incompetent or unscrupulous can easily ruin a restoration project. “It’s hard to find people who know how to do that kind of woodworking,” Ramia says.

By the end of lunch—and a brief-but-idyllic cruise on the Miles River—Ramia was smitten. He rushed home to research the history of the boat and the people who built her online. “To me, this was what boats and yachts are all about,” he says, recalling his reaction. Two years later, Ramia, who had recently earned his Coast Guard captain’s license, was looking around for a classic boat. He’d already begun making inquiries about available Trumpys when the owner of the Washingtonian, who’d heard about his search, called to offer him a deal that he said “you might not want to refuse.” Teaming up with DiPaula, Ramia snapped it up almost immediately and the adventure began.

DiPaula and Ramia weren’t exactly starting from scratch. The previous owner had told them he’d pumped nearly $1 million over five years into structural repairs, reconfiguring some of the cabins, and updating the electrical and plumbing systems. Still, it was clear there was more to be done.

For openers, the stern leaked, the rudders needed major rework, the hull was covered with barnacles, and the fittings were corroded. On the advice of a marine surveyor, the two decided to replace some of the planking and recaulk the teak deck. They rebuilt the windlass and upgraded the electronics. The living spaces needed redecorating and new furnishings—both the province of DiPaula, 59, who is an interior design consultant and restoration artist. And did we mention having to spruce up much of the old varnish and apply four new coats? “We realized that we’d have to re-do a lot of stuff that was done wrong,” DiPaula says.

One of the first challenges Ramia and DiPaula faced was finding a boatyard that could haul out a vessel that size and had experience working on wooden hulls. Few modern boatyards are willing to handle anything but fiberglass or metal boats. Putting your boat in the hands of a repair shop that’s incompetent or unscrupulous can easily ruin a restoration project. “It’s hard to find people who know how to do that kind of woodworking,” Ramia says.

The new owners finally hauled her at Tidewater Marine in Baltimore and hired two men who had worked for Trumpy in Annapolis to do some of the structural repairs. Ramia and DiPaula performed much of the cosmetic work, painting, and varnishing. “I cashed in a lot of assets, and Lee did, too,” says Ramia, a 49-year-old University of Maryland administrator, who took a six-month sabbatical to work on the Washingtonian. “We were spending 50-some hours a week fixing her up,” he says. “But rising costs were a continual frustration.”

The restoration went slowly. At the end, the vessel looked every inch the epitome of the luxury yacht of the 1930s with rich mahogany trim, both outside and in, sparkling white paint, and a club-like interior that would make anyone feel at home. Finally, in August 2005, the two men began operating the Washingtonian as a charterboat. Although the vessel had been Coast Guard-certified to carry up to 34 passengers, the owners limited their cruises to only a handful, hiring a captain to operate the boat and a catering service to provide the food. The business grew slowly as the company set up a website and printed brochures. Mainly, the news spread by word of mouth—a birthday party here and a family of Bay-watchers there. “It’s a limited, specialty market,” Ramia says.

The costs finally overwhelmed them. Ramia estimates that on top of the thousands the two spent to restore the boat, it would take about $100,000 a year to maintain and keep the boat and make further improvements. And that doesn’t include business costs such as advertising and brochures. “It was an eye-popper,” he recalls.

Halfway through the venture, the company suffered a setback when Maryland reaffirmed that it would bill them for excise taxes even though the boat was in the state only six months out of the year. They searched for grants and other sources of money but failed to find them. Finally, last October, they sold the Trumpy to a buyer in St. Augustine, FL, who has been operating it as part of a charter boat business.

The new owners finally hauled her at Tidewater Marine in Baltimore and hired two men who had worked for Trumpy in Annapolis to do some of the structural repairs. Ramia and DiPaula performed much of the cosmetic work, painting, and varnishing. “I cashed in a lot of assets, and Lee did, too,” says Ramia, a 49-year-old University of Maryland administrator, who took a six-month sabbatical to work on the Washingtonian. “We were spending 50-some hours a week fixing her up,” he says. “But rising costs were a continual frustration.”

The restoration went slowly. At the end, the vessel looked every inch the epitome of the luxury yacht of the 1930s with rich mahogany trim, both outside and in, sparkling white paint, and a club-like interior that would make anyone feel at home. Finally, in August 2005, the two men began operating the Washingtonian as a charterboat. Although the vessel had been Coast Guard-certified to carry up to 34 passengers, the owners limited their cruises to only a handful, hiring a captain to operate the boat and a catering service to provide the food. The business grew slowly as the company set up a website and printed brochures. Mainly, the news spread by word of mouth—a birthday party here and a family of Bay-watchers there. “It’s a limited, specialty market,” Ramia says.

The costs finally overwhelmed them. Ramia estimates that on top of the thousands the two spent to restore the boat, it would take about $100,000 a year to maintain and keep the boat and make further improvements. And that doesn’t include business costs such as advertising and brochures. “It was an eye-popper,” he recalls.

Halfway through the venture, the company suffered a setback when Maryland reaffirmed that it would bill them for excise taxes even though the boat was in the state only six months out of the year. They searched for grants and other sources of money but failed to find them. Finally, last October, they sold the Trumpy to a buyer in St. Augustine, FL, who has been operating it as part of a charter boat business.

Neither man has any regrets. “To be on that vessel would bring on a feeling of being so special and part of an era that doesn’t exist anymore,” Ramia says. “Lee and I were working owners of that boat. We knew how everything operated. It was a matter of great pride to us that we had turned her into the pristine example that she finally was. She was one of the finest-looking Trumpys of that era.” But, he adds, keeping a boat like the Washingtonian “is going to be a passion, and you have to be able to afford that passion.”

The bond between the boat and its former owners continues. Both Ramia and DiPaula have kept in touch with the new owner, providing an institutional history and even some advice when needed. Ramia still has photos of the Trumpy on the screen-saver on his office computer and has saved the brochures and the inevitable T-shirts from the venture. There are photos of the boat all over his house.

“She’s still very much a love of mine,” Ramia says of the Washingtonian, “and she’s still very much missed. I would encourage anybody who has a love of the water and fine craftsmanship to go into buying a classic boat, but you need to go into it with your eyes open. I’m thankful for the experience—it’s something I wouldn’t trade for the world. But it’s not an investment; it’s a labor of love. It will cost you triple what you intended.”

Neither Ramia nor DiPaula has given up the love of classic boats. DiPaula has bought a 50-foot Elco cruiser built in 1930 that’s faintly reminiscent of the Washingtonian and is restoring her with plans to “cruise up to New England for a while.” And Ramia is looking for another classic boat—this time in a “more manageable” range of 35- to 40-feet long.

Now, where were we again?

Neither man has any regrets. “To be on that vessel would bring on a feeling of being so special and part of an era that doesn’t exist anymore,” Ramia says. “Lee and I were working owners of that boat. We knew how everything operated. It was a matter of great pride to us that we had turned her into the pristine example that she finally was. She was one of the finest-looking Trumpys of that era.” But, he adds, keeping a boat like the Washingtonian “is going to be a passion, and you have to be able to afford that passion.”

The bond between the boat and its former owners continues. Both Ramia and DiPaula have kept in touch with the new owner, providing an institutional history and even some advice when needed. Ramia still has photos of the Trumpy on the screen-saver on his office computer and has saved the brochures and the inevitable T-shirts from the venture. There are photos of the boat all over his house.

“She’s still very much a love of mine,” Ramia says of the Washingtonian, “and she’s still very much missed. I would encourage anybody who has a love of the water and fine craftsmanship to go into buying a classic boat, but you need to go into it with your eyes open. I’m thankful for the experience—it’s something I wouldn’t trade for the world. But it’s not an investment; it’s a labor of love. It will cost you triple what you intended.”

Neither Ramia nor DiPaula has given up the love of classic boats. DiPaula has bought a 50-foot Elco cruiser built in 1930 that’s faintly reminiscent of the Washingtonian and is restoring her with plans to “cruise up to New England for a while.” And Ramia is looking for another classic boat—this time in a “more manageable” range of 35- to 40-feet long.

Now, where were we again?

About the Author: Art Pine is a freelance writer, USCG-licensed captain, and a longtime Chesapeake Bay power and sailboater.

About the Author: Art Pine is a freelance writer, USCG-licensed captain, and a longtime Chesapeake Bay power and sailboater.