The famed Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen once said, “Adventure is just another word for poor planning.” In Amundsen’s time explorers were very much on their own, without the support of a vast electronic safety net and boundless rescue assets, and as such, the best of them did everything in their power to avoid the unexpected; they had ‘everything in order.’

There’s something to be said for this approach, particularly where cruising vessels are concerned. As the manager of a busy boat building and refit yard for over a decade, and another decade as a

marine systems consultant, I’ve learned many lessons, both directly and via my clients.

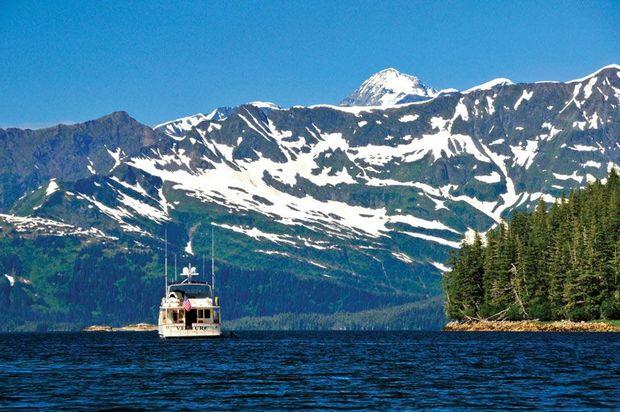

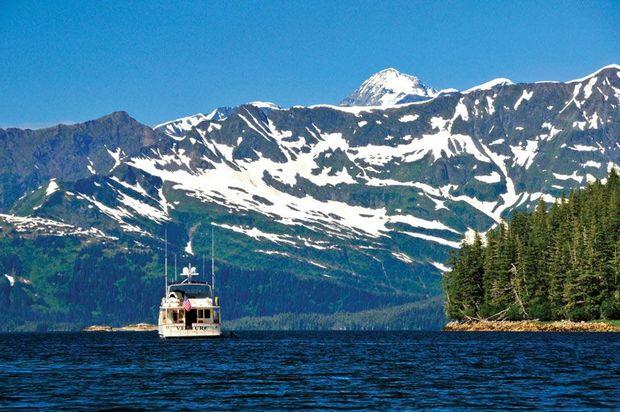

Several years ago, my wife and I, while transporting a customer’s 57-foot ketch from St. Michaels to Mobjack Bay, experienced an engine failure. I heard a change in the engine’s note and instinctively glanced at the instrument panel and noticed the volt meter was hovering just under 12. I knew something was wrong.

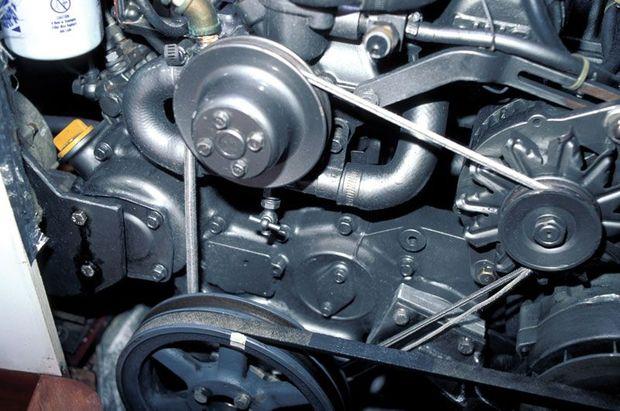

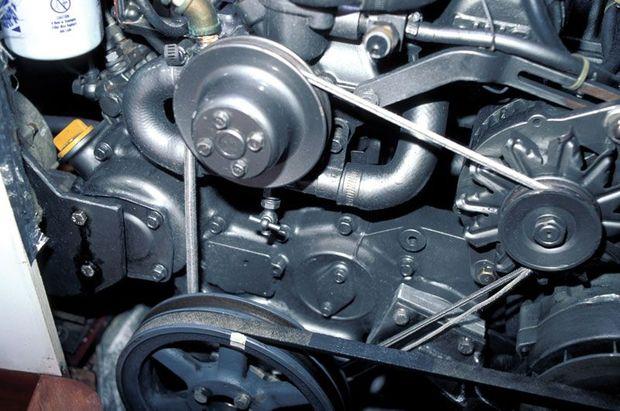

While my wife took the helm, I opened the engine box, where I immediately identified the problem. My heart sunk. Remnants of the fan belt hung in shreds from the front of the engine. We were well off the beach; winds were light, and so we ghosted along while I rummaged through the vessel’s spares locker for a replacement. While she was a 57-footer, she was used by her owner primarily as a day sailer, which meant her spares were limited to a few fuses and light bulbs and a quart or two of oil.

Lesson one learned: never leave the dock without at least a quick review of onboard spare parts, which should include among other things: impellers, belts, and fuel filters.

As I pondered our situation, I heard the sails begin to slat. The wind had all but died now, and what little of it there was wasn’t from a favorable direction. The ignominy of calling for a tow made that a non-option; when my staff back at the yard found out, I’d never live it down.

While there were no spares, I did have my well-stocked tool bag. After some head scratching I managed to make a “belt” from a triple length of 3/16-inch flag halyard, reinforced with electrical tape and zip ties. The zip ties didn’t last, however, after a few iterations the “Mark IV” version worked well, enabling us to power for several hours to a port where I was able to source and install a replacement belt.

Lesson two: always have a good set of tools aboard. At the very least always have a flashlight and a knife.

On another occasion, while cruising with a client off the coast of Newfoundland in heavy weather, several hours from the nearest port, the high water alarm sounded. I opened the hatch over the main bilge and took a face full of chilly North Atlantic brine; the stuffing box was doing a very credible imitation of a garden sprinkler on steroids. I closed the hatch and directed the helmsman to throttle back. Because of the sea state, it simply wasn’t possible to be without power for more than a few minutes. I asked the owner if he had spare packing aboard, and of course he didn’t.

I searched for a suitable alternative. We had plenty of line, but it was all synthetic. I was concerned it would melt and score the shaft, and none of it was small enough in any event. I finally decided I had what I needed to manufacture packing, a well-worn cotton T-shirt and cooking lard.

I cut up and rolled strips of T-shirt that equated the rough dimensions of waxed flax packing, and then slathered them with Crisco. Removing the remnants of the old packing and stuffing in the new, between bouts of seasickness and backing away when the helmsman signaled he needed to turn our head to the seas, proved a bit of a feat. Ultimately it worked, and we limped in at reduced speed to Harbour Breton, where a fisherman was kind enough to give us some packing material for which he’d accept no payment.

Lesson three, be prepared to improvise, and be thankful for the kindness of fellow mariners.

Amundsen also said, “Victory awaits him who has everything in order —luck, people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck.” Failures like those described are anything but bad luck, they represent nothing more than a lack of preparation, and are thus entirely avoidable.

Regardless of whether you’re setting off to cross an ocean, or just the Bay, first ask yourself what you will do in the event of a failure of a critical system, a belt, impeller, fuel filter, raw water hose or stuffing box. What will you need to carry out repairs, even if temporary? Only after you’ve answered those questions should you cast off your lines and get underway.

About the Author: Former boatyard manager, technical writer, and lecturer, Steve D'Antonio consults for boat owners and buyers, boat builders, and others in the industry. Visit stevedmarine.com for his weekly technical columns.

About the Author: Former boatyard manager, technical writer, and lecturer, Steve D'Antonio consults for boat owners and buyers, boat builders, and others in the industry. Visit stevedmarine.com for his weekly technical columns. There’s something to be said for this approach, particularly where cruising vessels are concerned. As the manager of a busy boat building and refit yard for over a decade, and another decade as a marine systems consultant, I’ve learned many lessons, both directly and via my clients.

Several years ago, my wife and I, while transporting a customer’s 57-foot ketch from St. Michaels to Mobjack Bay, experienced an engine failure. I heard a change in the engine’s note and instinctively glanced at the instrument panel and noticed the volt meter was hovering just under 12. I knew something was wrong.

While my wife took the helm, I opened the engine box, where I immediately identified the problem. My heart sunk. Remnants of the fan belt hung in shreds from the front of the engine. We were well off the beach; winds were light, and so we ghosted along while I rummaged through the vessel’s spares locker for a replacement. While she was a 57-footer, she was used by her owner primarily as a day sailer, which meant her spares were limited to a few fuses and light bulbs and a quart or two of oil.

There’s something to be said for this approach, particularly where cruising vessels are concerned. As the manager of a busy boat building and refit yard for over a decade, and another decade as a marine systems consultant, I’ve learned many lessons, both directly and via my clients.

Several years ago, my wife and I, while transporting a customer’s 57-foot ketch from St. Michaels to Mobjack Bay, experienced an engine failure. I heard a change in the engine’s note and instinctively glanced at the instrument panel and noticed the volt meter was hovering just under 12. I knew something was wrong.

While my wife took the helm, I opened the engine box, where I immediately identified the problem. My heart sunk. Remnants of the fan belt hung in shreds from the front of the engine. We were well off the beach; winds were light, and so we ghosted along while I rummaged through the vessel’s spares locker for a replacement. While she was a 57-footer, she was used by her owner primarily as a day sailer, which meant her spares were limited to a few fuses and light bulbs and a quart or two of oil.

About the Author: Former boatyard manager, technical writer, and lecturer, Steve D'Antonio consults for boat owners and buyers, boat builders, and others in the industry. Visit stevedmarine.com for his weekly technical columns.

About the Author: Former boatyard manager, technical writer, and lecturer, Steve D'Antonio consults for boat owners and buyers, boat builders, and others in the industry. Visit stevedmarine.com for his weekly technical columns.